For My children, Ari and Sharon, and For Theirs ...

by Elena Feder (Vancouver, Canada)

I travelled to Częstochowa in September 2016. It was the first time I set foot in the country where my parents were born; the land they fled with no desire ever to return; the world that took from them loved ones, their youth, dreams and aspirations, and irremediably destroyed their lives.

So strong was their rupture with the past, that they chose not to teach their children Polish, the language in which, in their eyes, unspeakable atrocities had been carried out. For them, the Polish neighbours with whom they shared a life had all but aided and abetted the murderous actions of their German masters. At home in Bolivia, I spoke Aymara and Qechua with my nannies, Spanish later at school. With my parents, it was always Yiddish, the mameloshen.

Thus it is no surprise that Poland was never high on my list of places-I-must-visit. Had someone asked me why I was going, I might have reasoned that Częstochowa was where my mother and her four brothers were born, that I knew nothing about their lives, and even less about the grandparents, great-grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins I may have had. My mother was not the garrulous type.

In truth, I hadn’t formulated any questions, let alone found answers to guide me out of the maze I unknowingly had set out to unravel.

I went as one of the 130 participants in the Fifth Reunion of The World Society of Częstochowa Jews And Their Descendants. The First Reunion took place in 2004, but I only learned of the Society’s existence a few months before going. The hook was a link on their website to The Return of the Violin, a stunning documentary that tells the story of how a 1713 Stradivarius, stolen from the internationally renowned violinist Bronisław Huberman at Carnegie Hall in 1936, returned sixty five years later to his native Częstochowa in the hands of its new owner, the legendary Joshua Bell1.

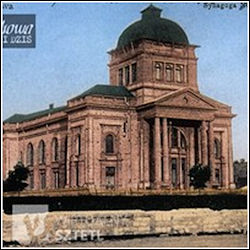

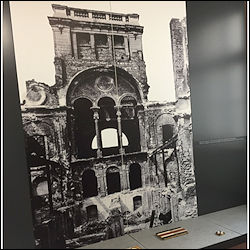

I was mesmerised by the story. I had heard that my grandparents owned a paint/hardware store not far from the destroyed New Synagogue where the concert hall now stands. Dots kept connecting. I decided to go.

The New Synagogue and (left) an architectural wonder burned to the ground by the Nazis in 1939.

The moment I set foot on the minibus connecting Warsaw to Częstochowa, I was transported onto the set of an unfinished movie running unheeded in the deepest recesses of my brain since forever.

The language was incomprehensible and my knowledge of the social, cultural and political histories of the land of my ancestors rather superficial. Yet it all seemed strangely familiar, uncanningly like home; even the language. The ten passengers on the bus (French, American, Australian and Canadian) felt like extended family. So did most of the people I would later encounter.

Unsettled, I looked out the window for clues to my inner landscape. Everything I saw had meaning only in context. The present was impregnated by the past. The endless birch and alder forests at the sides of the road conjured images of emaciated ghosts, running for their lives tattered and terrified, begging for mercy, pitilessly gunned down by uniformed Nazis before the sometimes cowered but mostly gleeful eyes of their old compatriots. I could hear their muttered cries, the words of the Shema fade softly with their dying breath.

I shared my thoughts with the others. To my surprise, they too had had such visions. We share the nightmare. We also share the desire to find ways of coming to terms with it. Each in our own way, we were piecing together the frayed remnants of a common past, hopelessly unaware where the road would take us. We later crossed paths at the Archives, shared our discoveries, supported one another when things got tough, celebrated everyone’s successes as our own.

The only Polish speaker in the group, a seasoned Australian on his fifth reunion (Webmaster: I suspect that was me.), asked the driver, on my behalf, if this modern highway had been built atop the old road between Warsaw, Częstochowa, and neighbouring towns like Radom, Kielce, and Pilica, my father’s hometown. No one knew.

My father left for Warsaw to study dentistry, his life dream, in the mid-30’s. Armed with determination and a good dose of chutzpah, he handed his parents his newly-minted rabbinical title (Smicha) – obtained to soothe their fears that he might become a goy – cut his payes, and departed with a younger brother for the big city. By the time the War broke into their lives, the modernised yeshiva bucher had become a dental surgeon, read Mein Kampf in German, joined Betar and enlisted as a medic in the Polish Army “Where else could I learn to use a weapon?”2. A photograph of my father in uniform, his infantry cap irreverently misplaced, his gloomy brother and proud fiancée standing behind, leaning on his shoulder, speaks volumes. Neither survived. He was barely twenty three.

My father never forgave his Polish comrades for handing the Jews over to their captors. “Even the Nazi officer shamed and scolded them!” A breach of military etiquette, I guessed. In my eyes, no one could ever surpass the cold-blooded, measured, industrious barbarity of the Nazis; not even their eager collaborators. Besides, Jews fared no better when their own lives were on the line. “It’s not the same.” End of conversation.

Back there, where stories and places were coming together, I looked for markers of my father’s occasional trips home to see family, footprints of memories somehow transferred to mine. Other than the occasional centuries-old house in a village or an odd crumbling farmhouse far afield, I found none. Bare landscapes mimicked the erasure of the past. The murder of six million Jews, nearly half of them Polish with roots a thousand years deep, had left behind a haunting void.

Częstochowa, an important centre of Jewish activity before the War, offered a slightly different story. The town attracted large numbers of Jews from neighbouring provinces since the late 1700’s and, despite the typical animosities and the occasional Pogrom, the community prospered in this deeply Catholic town. By the 1930’s, a disproportionate number of the elegant two- and three-storey late-19th century houses and businesses lining the treed boulevard that leads to the world-renowned Jasna Góra Monastery, were owned by the wealthier. Jews were so central to the economic, industrial and social life of the city that even the icons and prints – sold by the millions to Christian pilgrims who traveled great distances to see the miraculous Black Madonna – were produced by them.

It is said that Jews had also fared better than anywhere else in Poland during the war. Not so.

When the German Army arrived in September 1939, Jews comprised approximately one-third of a total population of 135,000. By the end of the War, of the nearly 45,000 Jewish residents – of which only 28,456 were accounted for by the Germans before relocation to the Big Ghetto, in the poorer Jewish area of town – fewer than 5,000 survived. Of the 5,194 Jews who walked out alive from HASAG the morning of January 17th 1945, only 1,518 had been Częstochowa residents before the War, a mere 1,240 native-born – my mother was one. Approximately 3,000 more survived other camp, like my unle Yacob, or as partisans. Not exactly a stellar record.

One reason given for the purportedly high survival rate was Częstochowa’s strategic importance to the Nazi war machine. Four of the six armament factories in HASAG’s defense conglomerate were built there.3 As recorded in the original German Government workers lists (where I found my mother and one uncle), during the five years the camps were in operation, the number of labourers grew from 4,734 to 10,990.4 Only 2,490 were Częstochowianin, the other 7,500 were “selected” following transfers from nearby villages and camps. In 1942 alone, more than 20,000 people were forcibly transferred from neighbouring towns, raising the Jewish population to over 50,000, which turned Częstochowa into the third largest ghetto in conquered Poland after Warsaw and Łódż.

The HASAG-Pelcery Slave Labour Camp

I will never know if my paternal grandparents and their five murdered children were among those transferred in 1942 to Częstochowa from Pilica – a shtetl with a population of 1,711 Jews and a history dating back to the late 1500’s. It would have been the closest they would have come to crossing paths with their future in-laws, fantasmagorically prefiguring the tortuous road that led to their survivor children’s marriage.

I will never know, because the Nazis did not bother to keep records of their names or the names of the hundreds of thousands gassed, shot and buried in Treblinka.5 From Częstochowa alone, 48,000 Jews were packed into trains and “processed” in this forgotten hell on earth between September 22nd and October 7th 1942. A bare two weeks. Daunting.

The train station exterior, as it looks today.

I lit a candle and said Kaddish when we subsequently gathered at the Umschlagplatz Memorial, a striking monument unveiled in 2009, a few feet from the ramshackle remnants of the fateful station. Created by the late sculptor Samuel Willenberg, a Częstochowianin who miraculously survived the July 1943 Treblinka uprising, the memorial’s simplicity belies the profoundity of its message. Rusted train tracks, removed from the nearby station, are fastened to a severed brick-and-mortar wall, on one side in the shape of a star of David, on the other, in two parallel lines. A weeping willow mourns quietly behind the crack. A copy of a daily train schedule protected by two tall pieces of thick glass stands to one side like a silent witness.

The 2016 Reunion Memorial Ceremony at the Umschlagplatz Monument.

It was created in 2009 by sculptor Samuel Willenberg z”l, a native of Częstochowa

and the last survivor of the Treblinka uprising.

Four survivors, present at the Reunion, were honoured on this occasion.

From left: Gavriel Horwitz, Marila Rotfeld, Ada Ofir Frajman, and philanthropist Sigmund Rolat

Glass sculpture containing the train schedule6, with the train station in the background.

As if on cue, a sudden burst of heavy rain briefly interrupted briefly the rabbi’s heartfelt rendition of El Malei Rachamim.7 The heavens, too, were crying. “Too little, too late”, I thought.

There were other events – a banquet dinner, a guided tour of Jewish landmarks, two magnificent concerts, the unveiling of an abstract rendition of a chamber quintet by Israeli sculptor Anna Huberman-Lazowski,8 and an evening at the Jan Długosz Academy,9 where high school students unveiled projects referencing the past and present of their city in relation to the War – moving attempts of come to terms with a history their young minds can scarcely comprehend.

Most memorable was our visit to the HASAG Pelcery slave labour camp, a massive brick and mortar compound bordering the city, dedicated largely to the production of bullets and military uniforms during the War (one of my mother’s tasks). Across the road leading to the camp, stood two or three 4-storey buildings where doctors and engineers lived in cramped quarters alongside seamstresses, tailors, shoemakers and other professionals selected to serve the whims and needs of their Nazi masters.

Left: HASAG-Pelcery interior viewed from the street.

Right: HASAG-Pelcery memorial – with business signs on either side.

Thousands laboured and perished behind its walls. It was disturbing to see new industries in operation, their signs afixed to window bars that open to empty rooms, decaying walls and dusty dirt floors, their loaded trucks cutting into this hallowed ground incessantly.

One of the survivors, the indomitable Sigmund Rolat (left), founder and supporter of the World Society, bore witness to the horrors. Shaken yet contained, he spoke of life as child in that vile site, punctuating the personal with vivid descriptions of the camp’s day-to-day operations. Here, he pointed cane in hand, the metal was pressed; there, bullets were molded, over there washed… crated… loaded… shipped. In that courtyard, he gently bemoaned, people were regularly shot, punitively or at whim

we watched from the kitchen. Each prisoner, he sighed, worked two daily shifts of ten hours on starving rations.

One of the survivors, the indomitable Sigmund Rolat (left), founder and supporter of the World Society, bore witness to the horrors. Shaken yet contained, he spoke of life as child in that vile site, punctuating the personal with vivid descriptions of the camp’s day-to-day operations. Here, he pointed cane in hand, the metal was pressed; there, bullets were molded, over there washed… crated… loaded… shipped. In that courtyard, he gently bemoaned, people were regularly shot, punitively or at whim

we watched from the kitchen. Each prisoner, he sighed, worked two daily shifts of ten hours on starving rations.

The accumulation of details fleshed out the horror and gave the unimaginable the weight of the real.

Rolat’s story is exceptional. Born Zygmunt Rozenblat to a wealthy Częstochowa family, he lost both parents, a brother, and his devoted Polish nanny in the War. When he was fifteen, he made his way to the New World by dint of wit, eventually becoming a successful entrepreneur with businesses in the U.S. as well as Poland after the fall of Communism. An art collector, music aficionado and philanthropist, with a mission to preserve Poland’s rich Jewish history, Rolat is a founding member of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, the main contributor to the annual Jewish Culture Festival in Kraków, and an ongoing supporter of the Częstochowa Huberman Philharmonic. Along with Alan Silberstein and Alon Goldman, Simund Rolat was the driving force behind the creation of the Częstochowa Museum of Jewish History, inaugurated with great pomp and circumstance during our visit.10

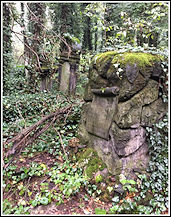

The Mayor of Częstochowa placed countless resources at our group’s disposal and spoke at practically every event, with particular eloquence at the highly publicised visit to the Jewish Cemetery. Established between 1799 and 1804, the cemetery is a testament to the long-term commitment of the community to its city. Though its 8.5 hectares now cradle fewer than 2,000 surviving gravestones, jostled by crawling roots, bedecked by moss, hopelessly cramped by tangled brushes and sky-defying trees, several newer monuments have been erected to honour War victims.

The Mayor of Częstochowa placed countless resources at our group’s disposal and spoke at practically every event, with particular eloquence at the highly publicised visit to the Jewish Cemetery. Established between 1799 and 1804, the cemetery is a testament to the long-term commitment of the community to its city. Though its 8.5 hectares now cradle fewer than 2,000 surviving gravestones, jostled by crawling roots, bedecked by moss, hopelessly cramped by tangled brushes and sky-defying trees, several newer monuments have been erected to honour War victims.

Germans and their collaborators wrecked havoc at the cemetery from their arrival in 1939 until 1943, a year mired by mass executions. On March 19th, six resistance fighters were executed against a wall11; the next day, German soldiers shot 127 no-longer-needed professionals and their families: doctors, lawyers, engineers, and members of the Jewish Council; the 26th of June, they destroyed the remaining Small Ghetto, murdering some 1,500 people; on the 20th of July, hundreds of slave labourers were executed. Children were killed en masse at different times. When the War ended, hundreds of mass graves were exhumed by survivors and given a proper burial.

One of the mass grave memorials. The plaque reads:

“In this very place, on July 21st 1943, Germans and Ukranians shot over 200 Częstochowa Jews.

With the passing of time, only these individuals are still remembered (names follow)”.

Frustrated by the rain and by the fruitless search for family gravestones, my cousin and I left for the City Archives (Archiwum Panstwowe). It was not our day. We leafed through countless birth and marriage records but found nothing. In truth, we had no idea what we were looking for, or where to begin. Our empathetic friends smiled in recognition.

The next day, armed with new resolve, we went on a mission to find Kozia, the street on our parents’ birth certificates (obtained by my brothers a year earlier). No.24 was nowhere to be found. The houses along the short block and a half are either old or decaying, or reduced to a crumbling wall devoured by overgrowth. The house of prayer on the corner had been converted to apartments. A supermarket touted gentrification.

One of several abandoned lots where houses once stood on ulica Kozia.

I remembered my mother talking about the Black Madonna. The Monastery is still as luscious and crowded, but the house where she and her family lived had disappeared with barely a trace. We were pilgrims without a shrine.

I felt the stone pavers under my feet, imagined mom as a child playing with friends, brothers, cousins, walking to and from school, accompanying her mother to the market, the shochet for Holidays. I scoured the area for houses she may have considered while running for shelter after her family was rounded up. Perhaps she returned, betrayed by the farmer who hid the blond, blue-eyed seveteen-year old beauty, in exchange for free labour and the two gold coins her father had hidden in her shoes. I thought of her languishing in HASAG, emaciated, worked to exhaustion. Sadness gave way to anger. It was time to leave.

I spent the last day with friends at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. Sifting through microfiched records kept by the Częstochowa Judenrat between May 1941 and January 18, 1942, I found my grandfather’s name on a list of workers and craftsmen, whose tools had been confiscated for the Nazis.12 His was a sewing machine (Naehmaschine). He did not own a painting store after all!

Moszek Hofman’s handwritten Judenrat entry

It bothered me that my grandfather’s was the only handwritten name on the typewritten pages. I set the thought aside. I imagined his sinewed hands working away at the old sewing machine, foot on pedal, his back bent over, the up and down motion of the needle giving life to shapeless cloth. Perhaps he was making a dress for his only daughter. Before I could fully image my mom proudly parading her father’s gift, joy faded into darkness at the realisation that ulica Kozia runs around the corner of the Old Market Square (Stary Rynek) in the Big Ghetto, the gathering place on the way to the train station a mere six blocks further, where her world would soon roll unabated through the gates of hell.

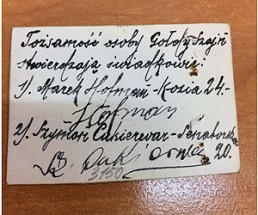

The archivist suggested I look through Częstochowa’s municipal records. Imagine my surprise when I found there an application for an identity card issued to my grandmother on May 31st, 1930. I pointed to the reference to an extant photograph on the microfiche. The archivist examined the screen in disbelief and ran to fetch the original. He returned with a small dark sepia photograph attached to the original yellowing document. The room was abuzz with excitement. I was dumbfounded.

No pictures of this side of the family had survived the War. Had I struck gold? The document revealed my grandmother’s and grandparents’ official first and last names (not the Yiddish ones I was given), the time and place of her birth (not Częstochowa), her avowed profession (worker), the colour of her hair and eyes (grey, like mine).

Front and back of Photo for Golda Hofman’s Identity Card

I searched the photograph for more clues. The young woman staring at the camera was clearly not used to having her photograph taken. Her gaze is stern yet quizzical, her body stiff but relaxed. I had imagined her a babushka. The solid, curious, assertive woman in the short-sleeved and relatively low-cut dress was everything but. I saw hints of my mother in her, my cousin saw her father.

The back of the photograph opened yet another door. My grandfather’s signature, certifying the identity of his 27 year old wife, jumped out at me like a bolt from outer space – a palpable remnant of his physical presence at a specific place in time. I was relieved that the rudimentary scrawl did not match the handwritten entry in that Judenrat list. I wouldn’t want to think of him performing that thankless role. The photograph had had a big impact, but the handwritten name had surpassed the mechanically reproduced image’s immediacy by far. I could smell the paper, touch the protruding ink and, through both, him. It is the closest I ever got to any of my four murdered grandparents.

Guided by the belief that I owe “never again” to my children and their children’s children, when my father died I made the decision to leave the study of the Shoa to historians and other experts and to direct my efforts, instead, to help curb the resurgence of Jew-hatred in the future. I wrote letters and articles, joined organisations, sat on boards, sought out innovative solutions. After eighteen years, all I saw was the multi-headed hydra rising again, safe places dwindling. My trip to Częstochowa was an attempt to understand why.

While that question still begs and answer, I learned that I was wrong to think I could skip the past. Not because it has the nasty habit of returning in different guises. One can live with ghosts forever without knowing it, but healing can only come from fleshing them out, endowing them anew with life through the work of re-remembering, of piecing together fragments of their truncated existence, touching walls, walking on cobblestones, cleaning the moss off gravestones, reaching out beyond dense-dark anxieties and fears to find moments of rest, maybe even deliverance.

We can only mourn a loss we make our own.

My mother, Sura/Sala Hofman, was born and raised in Częstochowa. My parents married in Germany after the War and left for Bolivia, pregnant with me. There, they raised a family, while recovering from undiagnosed and untreated PTSD. They immigrated to Vancouver shortly after I did. Both are buried here.

SUBMIT YOUR OWN STORY!

to learn how!

About the Author:

Elena is an independent scholar, theorist, critic and curator of Film and Media Arts. She holds an M.A. from the University of British Columbia and a PhD in Comparative Literature from Stanford University. She is the author of several articles published in magazines, academic journals and book collections.

Elena is an independent scholar, theorist, critic and curator of Film and Media Arts. She holds an M.A. from the University of British Columbia and a PhD in Comparative Literature from Stanford University. She is the author of several articles published in magazines, academic journals and book collections.

In addition to teaching, she has curated film and video programs and organised conferences, both nationally and internationally, with the support of both the Canada and British Columbia Councils for the Arts, as well as the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. She was Humanities Fellow at Stanford and founder and Executive Director of Americas on the Verge Society for the Advancement of Arts and Culture in Vancouver.

Born in Bolivia, with survivors of the Shoah as parents, she currently resides in Canada. She has served on the executive of the now-defunct, BC Campus Action Coalition, the first Canadian organisation aimed at identifying and supporting efforts to resist the growth of antisemitism on university campuses, also acting as liaison between this organisation and the Canadian Friends of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre.

Her work is increasingly focused on a number of initiatives aimed at curbing the resurgence of antisemitism worldwide.

Author’s Notes:

1 Huberman, who escaped Europe for British-controlled Palestine, founded the Palestine Symphony Orchestra in 1936 (renamed the Israeli Philharmonic in 1948) largely to rescue, in a desperate and undoubtedly heart-wrenching effort, some 1,000 musicians and their families from certain death. In a revival of some sort, Bell chose to play the Brahms Violin Concerto (played for Brahms by Huberman when he was nine) on the recovered Stradivarius with the Częstochowa Philharmonic at the World Society’s Third Reunion in 2009. The world-class Częstochowa concert hall was officially renamed the Bronisław Huberman Philharmonic Hall on that occasion.

2 Research into the history of Jews in the Polish military has barely began. Most joined, if allowed, in response to Zev Jabotinski’s passionate entreat, to flee or to take up arms, in speeches delivered in Warsaw to tens of thousands of beleaguered coreligionists on three separate, historical occasions – 1936, Tisha B’Av 1937 and 1938.

3 A state-sponsored corporation, the acronym “HASAG” stands for Hugo Schneider Aktion Gesellschaft. HASAG Pelcery, Warta, the Raków steel mill, and the Częstochowianka plants where built within Częstochowa. The other two were HASAG Granat Werke in Kielce and HASAG Skarzysko-Kamienna. Each was devoted to a different aspect of the military enterprise.

4 This number was corroborated by the survivors in the last year of the War.

5 It took never more than three hours to “process” each man, woman, and child into one of the ten gas chambers working simultaneously 24/7. Between 800,000 and 1,200,000 unnamed Jews (and an undetermined number of Roma), continuously transferred to Treblinka as the “inventory” dwindled, were gassed, shot, and buried in mass graves at the camp – up to 15,000 per day. Himmler ordered the camp closed in 1943, after the grounds were razed by fires set by heroic inmates led largely by Częstochowa natives. In a partially successful effort to hide all evidence of his crimes from the advancing Soviet Armies, he personally oversaw the exhumation of 700,000 bodies. Inmates, who did the dirty work, witnessed the large heaps of bodies on pyres burning for months. Imagine.

6 The timetable of the death train from Czestochowa to the extermination camp in Treblinka. It departed from the Warta freight station on September 22nd, 25th and 28th, and October 1st, 4th and 7th 1942 at 12:29 pm to reach Treblinka at 5:25 the next morning. At 10 am, when the train was scheduled to leave for Częstochowa, out of the 7,000 people in the transport only a few men chosen by the Germans to work in the camp were still alive.

7 “God, full of compassion” – a prayer for the dead, especially martyrs, with roots tracing back to the 1648 Chmielnicki pogroms.

8 A relative of Bronisław Huberman. The Częstochowa Philharmonic was dedicated to him at the 2012 World Society Reunion.

9 A prestigious tertiary education institution named after a 15th century Polish priest and true Renaissance man.

10 A treasure trove for visitors and researchers alike, the Museum occupies the main floor of a beautifully restored, neo-Gothic palatial mansion built ca. 1910, on the somewhat seedy but central Kateldrana Street. Owned by two or three Jewish families before the War, among them Alon Goldman’s maternal grandfather Jacob Czarnylas, the former home now serves several social functions. The Museum, which covers the entire main floor, was created to permanently house the exhibition Jewish Life in Częstochowa, on tour since 2004. Curated by Prof. Jerzy Mizgalsky and designed by Prof. Andrzej Desperak, it spans three centuries of Jewish contributions to all aspects of life in the city, with particular emphasis on the years following the Nazi occupation and the 20th century events leading up to the War.

11 Częstochowa was reportedly one of three cities in Poland where Jewish Fighting Organizations were set up during the War.

12 Judenrat, a Board of Elders approved by the Nazis, was assigned the job of documenting public events: police reports, robberies, upheavals, fires, lack of public services, etc.