My Częstochowa

by NOA YALON LOWI (Israel)

Background

Yosef (Yosek) and Esther (nee Mendelowicz) Fridman both grew up in Częstochowa, in parallel streets, a few minutes walk away.

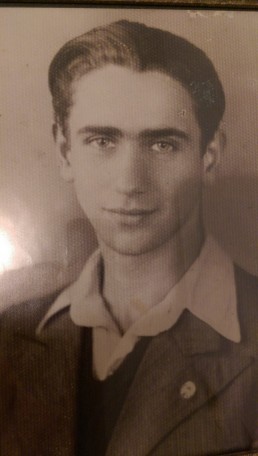

Yosek was born in 1916 in Częstochowa and lived ul. Garncarska. His father died when he was still quite young (long before World War II). Esther was born in 1917 in Krzepice and, while still a child, her family moved to Częstochowa and lived ul. Targowa.

Yosek and Esther both joined the Gordonia movement, and later, after the Hachshara, immigrated separately to Palestine – Yosek in 1938 and Esther in 1939.

Yosek had six brothers. The eldest, Dubcha (David), was invited to the United States. He emigrated, married and remained there until his death at a ripe old age. All other five brothers perished in the Holocaust, together with his mother and the rest of her family – three brothers and two sisters.

Two of Esther’s brothers, Yitzhak and Chaim, immigrated to Palestine in the early 1930’s. Esther’s illegal immigration to Palestine was financed by her brother Chaim and she remained grateful to him all her life. Another brother, David, survived the HASAG forced labor camp in Częstochowa and immigrated to Israel after the War. All her brothers, her parents and her other relatives perished in the Holocaust.

Yosek and Esther attended a training camp in Givat Ada and, shortly after, moved to Ma’aleh Hahamisha, where they originally intended to go. They then moved to Bnei Brak, where they decided to start a family out of a desire to raise children. During World War II, Yosek enlisted in the British army. In 1945, their daughter Nitzana was born, followed by their son Aviram in 1950.

Yosek and Esther were my grandparents (my mother is Nitzana), I am the Third Generation of the Częstochowa family living in Israel. In July 2017, I traveled with my family to Częstochowa.

My Trip to Częstochowa

My writing has been blocked, Ever since the visit in Poland.

Something has been thrust, something is blocked.

Something is choked inside and won’t come out.

What happened there? We knew all along that the majority of the Granny’s and Grandpa’s families had perished. That wasn’t a surprise.

We knew about the Holocaust.

We didn’t that think we’d discover a happy ending, something which history had forgotten to tell us about.

So, why this freeze? We hadn’t visited any of the extermination camps. We hadn’t seen harsh sights – not extremely harsh.

We simply went to visit the city where they had grown up and which we had been told about. But it actually began with a suffocation almost from the very first moment.

With excitement and sadness, we arrived at Częstochowa. As we approached the station and saw the “Częstochowa” signs through the window of the train, The heart raced, pounding, as tears climbed the throat, commencing their way out. We got off the train.

As I walked, trying to trace the sign I saw from the train to get closer and photograph it (as well as allowing my tears to burst out), We were welcomed by wonderful Małgosia and Marek, our warm and fantastic, guides whom we had hired to show us around all the places which we wished to see. They smiled broadly and warmly at us, as they held out their hands to help us down from the train. We found ourselves smothering our tears, swallowing them in order to greet them nicely, introduce ourselves and thank them for waiting for us with such devotion.

This blend of genuine gratitude and fought-back tears arouse caged anger and frustration. I felt, “I wanted a moment to digest and process it all and to meet you marvelous people five minutes later and not precisely now.

And you were so lovely and generous,you aren’t the source of this anger nor the shoulder to cry on. Thank you and it’s not fair. Why couldn’t you have been late a few minutes?

And so here began the journey to the past, to the city and to its civil registry and archives where the keep the birth certificates. Actually, when Auntie Macha was born and when Grandpa was born, Częstochowa was still under Russian rule and the documents were probably in Cyrillic. So doubts arose as to exact spelling and whether the documents will be found. And also, in those days, the registry was not necessarily done on the actual date of birth at all. This was not very common.

A beautiful, elderly woman arrives, waiting her turn. I wonder if she was born here and if she knew Granny or Grandpa. Maybe they were friends, maybe and maybe and maybe. And even if they would have met. Who knows if they would remember each other and, even if they did, who knows if they would recognize each other, even if I had a picture here with me of them from those days. Still, even if they did know each other, what issues would it raise? So they knew each other.

To be honest, she looks younger than my grandparents, even if they were still alive. It turned out that every senior I’ve seen sparked those questions in my mind, time after time. The odds are that they are probably younger than them. But surely, these people were here and experienced and witnessed the Holocaust in one way or another. They are a piece of history walking in front of me and their faces seem stiff and severe. Faces which had seen things that nobody should see nor experience nor should be recorded in the history of mankind.

And even if they were here, which side were they on? The monstrous? The escaping? The compassionate/human/saviors? The indifferent-numb towards this sickly horror? Perhaps they’re former Jews who managed to flee and prefer not to remember they were Jews at their younger years nor to remember some more things, some years in the pages of the history of their own personal life.

We continue to the Jewish cemetery to see the tomb of my great-grandfather, who was lucky enough not to know what future would bring upon his family. A neighborhood of ruined graves hidden within a frightful, dense, ivy jungle. Green, beautiful, creepy and bothering. Some of the graves are broken, some are destroyed, some are perforated by bullets and some of them only display damage brought about by nature.

We are surprised by the three mass graves of the community remnants who were not transported to Treblinka due to some calculation errors. Apparently, Nazis, too, mess up their calculations. So they brought them here, the single one sight which we considered as “holocaust free” and corrected their errors: The Nazis handed them shovels and firstly commanded them to destroy graves. Once the first mission was accomplished, they were commanded to dig an enormous pit and stand lined along its edge.. and…… SURPRISE!!! Here we are now, standing at this same spot!

The gravestone of my great-grandfather Eliezer Lipman Friedman in the Jewish cemetery of Częstochowa

This was not simply a cold and sick attitude by those who were following orders to slaughter – similar to slaughtering chickens or cows as if they were objects or products. There was emotion here. There was pure wickedness, cruelty and pleasure from the taste of blood and agony and grief and humiliation. The emotion of the kind which I want so badly to believe, does not exist in the world – even though I know it does, even though it was nothing new, even though variations of this unbelievable horror keep occurring on the planet.

But, suddenly, it was so close, personal, tangible, surprising and heart-rending. And we were standing here, without any clue as to whether our great-grandparents lay here beneath our feet, all my mum’s uncles and aunts or the rest of the family. Were they in one of the two mass graves, or in one we were shown later on that day at a green grass plot at Kawia street? Maybe they’re here. Mum pats the grass in silent tears.

Maybe they are in Treblinka. Maybe they were counted and ended up on the intentional transport lists. Maybe they were at the beautiful New Synagogue which had been burning for a whole week and was guarded by the Nazis to prevent extinguishing the flames. Maybe they randomly pissed off some Nazi soldier on the street and were shot for all to see and to beware. How are we supposed to find out what on earth happened to them? And, what difference does it make??

But for some reason it does matter. The heart desires to know, to address the sorrow and to shepherd the sadness to its rightful place. It is unclear why.

Maybe it is the will to deliver to them the belated message that we care, that they were loved and are mourned, that they were remembered, missed and thought about – even if they didn’t see or feel it, even if all they saw was alienation, numbness and indifference to death, suffering, sorrow and anguish, even if no one stopped when they fell and reached out a hand or at least parted. And also that there is still love in the world, although love is yet to win at all battles and we’ve yet to learn and change sufficiently- There is also love in this psychic world and there probably always will be.

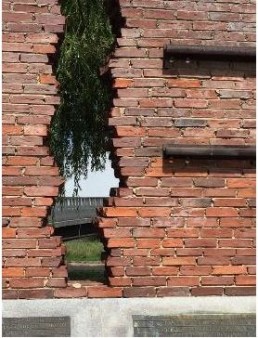

We go to what was the Jewish quarter and reach the streets where my grandparents had lived and grew up. – two parallel streets, the houses, not large within three minutes walking distance apart. It seems most of the houses have not been renovated since that time. In Grandpa’s street, where lived next door to his cousins, there were three houses side-by-side – one of which is now missing. It is the only one on the street missing, as if the earth had swallowed it up. There is no trace of it. Wild vegetation grows between the two houses of the family. We don’t know if the missing house belonged to Grandpa and his family or perhaps it was the existing house, which now houses Polish tenants who look at us with displeasure.

And there are warehouses in the garden of the building, windowless, with wooden doors which turn out to be people’s homes. Who live there today. It is not abandoned and, even though it appears to be a warehouse, it isn’t. My imagination blends with memories of stories going around in my mind. We arrive at my grandmother’s house. Well, not really as Grandma’s house also turns out to be the only one missing in the street. It also was gone. Why? What happened to those two houses in the Jewish streets?

We go to the river where Grandpa, as a child, used to fill a bucket with water to bring to his mother. Her picture hangs in my parents’ living room and flickers in our minds as we walk around here. With excitement, my father recalled what Grandfather told him- that once, in winter, he brought his mother water from the river and, by the time he’d returned with the bucket, walking only a few minutes, the water had completely frozen.

I’d heard that story more than once and when we reached the point where he used to fill up the bucket with water for his mum, we discovered that this is the very place where a memorial now stands commemorating the Jews who were sent to Treblinka, from this site, in six transports of freight trains. It was here that they stopped in the railway tracks passed, precisely here. Perhaps the family had been led here and had never imagined such a journey to their bitter end, as the French and Belgian conscripts who had passed through here and were warned and had not believed and refused to get off the train, despite warnings from the locals as to what awaited them.

The monument commemorating the Częstochowa Jews who departed from this railway platform on six transports to Treblinka. In the photo above, on the right, the train station building is decorated with a mural created by Częstochowa Fine Arts students. Below right shows the schedule of the six transports which left for Treblinka between 22nd September 1942 and 7th October 1942.

Perhaps some of them were at the Jewish hospital. hospitalised sick and found themselves crushed to death while they were confined to bed. My great-grandmother was already over fifty at the time. Who knows? What are these annoying, abusive questions and why are they not letting go?! Enough! They are gone! All of them! Long time ago! And it did not happen by nature whatsoever.

Touring the two former Jewish market squares showed nothing, just old sidewalks and squares empty of people or a memory of commerce or of life of any kind – just an exercise for the imagination, reinforced by photographs in the Jewish Museum. There was nothing new there either. It was the same in the residential neighbourhoods. It was as if time had frozen, as if they had not moved on and were still horrendous mementos, eternally in dreadful disgrace.

My Dad had been dragging his feet, right from the very beginning actually and grumbled, “Enough of death and depression. Let’s go to the river or to a cafe or a restaurant”. We didn’t understand and we were secretly angry at how could he shut himself with such insensitivity towards us and the guides, who had gone out of their way so to arrive all the sites associated with our grandparents and which we wanted to see. In retrospect, it is clear that it was precisely his sensitivity that led him to beg “enough!”. It had become too painful. The guides were wonderful, sensitive and supportive and hearty, gentle people and giving generously, with all their heart, all the information for which we asked.

Pain and sorrow piled and burned in our hearts and souls.

Thoughts and questions kept pecking my mind:

Why couldn’t we have supported Grandpa. He never talked about this. Why weren’t we there for him? I wished that someone was and had talked to him and processed, with him, all of the inferno and the guilt he experienced.

No one was saved from the Holocaust.

No one who was present, saw it and managed to survive and escape.

Not even those who emigrated before and “only” their whole family stayed behind and perished.

Not even the residents of other countries which the Nazis had not yet reached.

Nor the second generation which grew up without grandparents or uncles, whose parents were traumatised.

No one was saved from the Holocaust.

The entirety of humanity was deeply wounded by this inconceivable event committed by its own hands.

We tour Częstochowa and there is a lot of documentation and monuments and also respect relating to the community which had once lived there and to its history. But there is no trace of life here – just voids and cavities that have been opened in whole streets which have been damaged and have not been renovated all these years, in homes that are missing, in the monuments, in the deserted HASAG’s, in the pictures of the important and beloved figures we didn’t know, nor hear their voices. We were only told about most of them did not even see their pictures.

And there is no sign of life

And nothingness

And nothingness

And empty and burning.

LEFT: Ulica Targowa – Grandma’s house is not the only one missing on this street.

RIGHT: The staircase in the building where Grandpa may have lived in one of the apartments – downstairs, upstairs, who knows? Maybe in the courtyard.