The Częstochowa Ghetto

I. The Establishment of the Ghetto

The concept of enclosing the Jewish population in assigned districts became a reality after the Germans gave up such unrealistic plans as transportation to Madagascar.

In the Radom precinct, such districts were created relatively early. Indeed it was already possible to notice the first fruits of this German decision in the last months of 1940 (November – ghetto in Opocznie, December – ghetto in Tomaszów Mazowiecki). Having started only in the spring, by the summer of 1941 it had spread throughout the whole precinct.

In accordance with the general order of the Radom Lascha precinct boss, the biggest ghettoes were created in April 1941 – in Radom, Kielce and Częstochowa and smaller ones in Busk, Chmielnik, Ostrowiec, Rawa Mazowiecka, Starachowice, Nowe Miasto.

Already by 1939, the German authorities had created the new administrative districts of the Częstochowa region. As a result of these changes, the greater part of the Jewish population found themselves beyond Częstochowa on territory directly connected to the Third Reich. At that time, two towns – Krzepic and Kłobuck – had the biggest clusters of Jewish population in the whole administrative district. Jews who at that time, were living in areas of the new Reich apparently could remain – whilst the whole Polish population was to be transplanted to the General Government area.

However, SS Reichsfuhrer Himmler’s order (29/11/1939) that “Jews and Poles, who had been ordered to move from some area of the Reich to the GG and who despite this still remained in German Reich territory, were to be summarily shot”, caused an inflow of Jews into Częstochowa already by the beginning of 1940. Many of them also thought that they could adjust their lives to the change of location.

The German plan to exterminate Częstochowa’s Jewish population (and in other Polish towns) was based on the gradual preparation of the German “death machines” for the Final Solution.

In 1940, regulations were issued which became the legal basis for creating Jewish residential areas.

In Częstochowa, German preparatory work started at the beginning of 1941. Its goal was, as ordered by Stadthauptmann Wendler in March of that year, the creation of a Jewish residential district by 9th April.

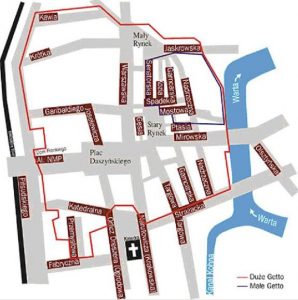

This order also specified the streets which were to be contained within this new adminstrative section of the town. The residential district to be enclosed extended around Daszynski Square, the Stary Rynek (Old Market) and the Warsaw Market. The railway line formed the boundary to the west; the Warta River to the east; to the north, ulicy Kawia, Kiedrzynska and Jaskrowska; and to the south, ulicy Fabryczna, Narutowicza and Strażacka. All Jews who lived outside this ghetto area were forced to move into the Jewish district by no later than 17th April 1941. At the same time, all Poles had to leave the area.

II. The “Big Ghetto”

This newly-created district was popularly known as the Big Ghetto. Its entrances were mainly guarded by OD-men, members of the Jewish police force. From the very beginning, the German authorities took extraordinary steps to isolate the ghetto inhabitants from the rest of the town.

Near the entrances to streets leading out of the ghetto were erected signs which warned Jews against leaving the district. They stated that leaving the ghetto without permission incurred the death penalty. Later, signs were also erected which threatened the death penalty to any Poles trying to enter the district. Black notices, on a yellow background, also warned of the risk of the contracting plague. The German authorities’ next move, by which they intended to hermetically isolate the ghetto, was to extract Katedralna and Strazacka Streets from the ghetto’s boundaries. In this way, the area of the ghetto became, on the one hand smaller and, on the other, considerably more densely populated.

It is difficult to determine the exact number of people living in the area of the ghetto. According to official statistical data, the number of Jews in Częstochowa at the time was around 40,000. In the summer preceding liquidation of the big ghetto, after the influx of Jews from the surrounding area, that number exceeded 50,000.

III. Extermination and Selections – The Liquidation of the “Big Ghetto”

After the Wannsee conference, the machinery was systematically prepared to serve one purpose – the extermination of European Jews. After all the organisational arrangements and the construction of the instruments of death in such camps as Auschwitz, Bełżeć, Majdanek, Treblinka or Sobibór had been completed, Himmler inspected them personally in the middle of July 1942. He then proceeded to the headquarters of “Operation Reinhard” in Lublin and discussed, with Globocnik, further plans for their genocidal activities in the General Government. As a result of these discussions, on 19th July 1942, he issued, from Lublin, secret orders to Wilhelm Krüger HSSPF in the General Government. That document determined 31st December 1942 as the beginning of cleansing the whole of the General Goverment of Jews

From that time, Jews only had the right to live in the so-called Stammlagern, i.e. collective camps located in Warsaw, Kraków, Częstochowa, Radom and Lublin. Only in specifically nominated places could selected Jews stay who were working for the requirements of the army.

In Częstochowa, preparations for extermination began prior to the events described above that had a more general scope. In June 1942, the Jewish Council (Judenrat) received, from the Stadthauptmann, an order to supply a precise new plan of the Jewish district with each individual home designated. They also nervously observed how the corners of homes and entrances to flats in cellars were being painted over with white paint. By the middle 1942, Jews were removed from a part of ul. Kawia, because there was to be established there a cemetery for future victims. Homes in ul. Garibaldiego were emptied to make room for future storehouses to contain plundered Jewish property.

The last stage of preparations to this final act of genocide was played out at the beginning of July 1942. The city authorities issued orders for a general roll call, designated for 3.00pm, at which all ghetto residents aged 16 to 60, from specified streets, were to be present – including members and associates of the Judenrat and the Jewish police. The order only excluded staff of the hospital within that region. As was later revealed, this entire exercise was a general trial exercise. prior to the planned September operation to liquidate the Big Ghetto of Częstochowa.

At 3.00am, 22nd September (on the Jewish holyday of Yom Kippur), the street lights were turned on, even though at that time, for reasons of economy they were dimmed at night to darkness. Jewish police units were summoned to immediately station themselves on the Metalurgia factory grounds at ul. Krótka 13. An hour later, with the police at the square, they received an order from the German officer in charge of the operation, for all residents from ulicy Kawia, Koszarowa, Krótka, Garibaldiego, Wilsona and Warszawsk, as well as parts of ulicy Garncarska and Nadrzeczna, to assemble by 6.00am in front of the factory.

They were required to bring with them their Work Card (Arbeitspass), in order to be checked by the German authorities. Shortly before 6.00am, panic broke out amongst those gathered. A group of forced labourers gathered near the exit of the ghetto. Herded from place to place by their guards and by soldiers in black uniforms, they attempted to move elsewhere. The first shots were fired, the first were wounded and killed. After a short time, the situation was brought under control. Soldiers from the Black Battalion slowly encircled the square. Methodically, they systematically finished off the wounded, even those who could still manage to stand and rejoin their companions.

After 6.00am, in ul. Krótka, a column of many thousands form. Women, men, children, the old and the young, the healthy and the sick – all wait with uncertainty for what fate will bring them. Nearly all hold their Arbeitspass. Each crosses the square where the selection happens – this takes several hours. Over 7,000 people were condemned to death. Around 350, thanks to their usefulness to the Third Reich armaments industry, would enjoy life for a while longer.

At midday, black-uniformed soldiers formed marching columns of five-abreast. Seven thousand people head towards the ghetto exit, crossing ul. Piłsudskiego in the direction of Zawódzie and only stop at the Częstochowa-Kielce railway line. A ramp had already been erected and a long train consisting of 60 cattle-wagons was waiting. An hour later, the doors to the wagons were closed and the train left in the direction of Treblinka.

On the ground, in puddles of blood, numerous corpses remain. At ul. Krótka 13, the square is cleaned. Numerous Jews gather approximately 200 bodies from the ground and, in wheelbarrows, cart them onto trucks. The bodies are then thrown into a large hole in ul. Kawia which had been prepared for the purpose earlier.

Further stages of this drama were played out on 25th-26th as well as 28th-29th September, barely a few days after the first “deportation”.

Subsequent operations take place faster and more easily than the first. Instead of gathering people as previously in the factory on ul. Krótka 13, specific blocks were combed by units of soldiers. The residents of designated homes were driven out into courtyards and, there, the final selection took place. The Germans informed members of the Judenrat that the deported Jews are bring taken to labour camps in Polish territory where they will work for the benefit of the Reich.

On 28th September, on the day prior to the third selection, green German police cars drive through the ghetto. Through megaphones, they announce that all Jews sent earlier by train had arrived safely at their destination, were feeling well and had commenced work. It was also officially broadcast that all Jews from the ghetto area, who were to assemble on the following day at the designated place, would receive half a kilogram of bread, marmalade and a bowl of warm soup.

That successful approach resulted in many hungry Jews reporting for selection of their own freewill on the 29th. This time, the authorities kept their word and distributed the promised food. However, there were many who did not believe the German authorities. These remain at home, but are removed from their homes amid screams and at gunpoint. During this third operation on 28th-29th September, the following streets were “cleansed”: Nadrzeczna, Garncarska, Targowa, Prosta and the Stary Rynek.

On 4th October, the next-to-last operation took place in the “Big Ghetto”. It encompassed, among others, “Dom Frankiego” on the corner of I Alei and ul. Wilsona, where the Germans, in April 1941, had housed the best Jewish artisans who were often forced to provide various services for the benefit of the Germans. (Jews called this building “The Artisan House”).

On that day, no more than 1,000 people were selected. A large number of ghettto residents, who had previously avoided being deported, were now caught, whereas earlier they had hidden in basements, in attics or behind fake walls in deserted apartments. The majority of those rounded up on 4th October were marched under guard to the train. With this transport, the last members of the Judenrat as well as half of the Jewish Police depart. The result of this Deportation Action was 40,000 Częstochowa Jews were transported to their deaths in Treblinka. The number killed on-the-spot was never accurately determined, but is estimated at around 2,000.

These specific operations actions were carried out on 22nd, 25th and 28th September, as well as 1st and 7th October 1942. The victims were transported by train to the camp at Treblinka.

In the Częstochowa area, the Germans left approximately 5,000 of the healthiest and strongest Jews alive, who were to be utilised for work in several factories, especially the HASAG munitions facfdtory, where several thousand Jews were forced to work.

V. The “Small Ghetto” – Częstochowa Forced Labour Camp

The Small Ghetto was created almost immediately following the deportations from the “Big Ghetto”. Approximately 5,200 Jews remained there – those who had survived the bloody events of the end of September and the beginning of October. They were squeezed into houses in a few streets which lay in the north-eastern section of the old Big Ghetto. The so-called Small Ghetto encompassed within its area ul. Koziaand parts of ulicy Nadrzeczna, Mostowa, Spadek and Garncarska.

|

It was located in one of the poorest and oldest districts of the city, long-inhabited by the city’s poor. All the houses in this area were small, toilets were mainly located in backyards and in many buildings there was a lack of running water. Only one street was asphalted, some were cobblestone, but most were covered in gravel. The area of the “Small Ghetto” was surrounded by a barbed wire fence approximately 2 metres high. Houses located near the fence were emptied, as were the shops. |

The only exit from the ghetto was located at ul. Garncarska. Opposite the exit lay the Warsaw market to which, every morning, the Germans responsible for the work groups came in order to collect Jews who were designated for work.

In very centre of the ghetto, in ul. Garncarska, was the Jewish Police building and a small hospital. Officially, none of the Germans used the name Small Ghetto – in all German documents and noctices, the phrase Forced Labour Camp Częstochowa was used. It was only a matter of formality. The creation of a new Jewish residential district accompanied the “cleansing” of the old Big Ghetto. It took approximately two weeks.

At this time, the Germans concentrated their efforts on two types of operations.

The first of these was the gathering of property abandoned in Jewish homes.

In the big building at ul. Wilsona 20/22, which formerly had housed the Lewkowicz Furniture Factory, a large workshop was established.

From amongst the Jews, groups of trademen was chosen – painters, locksmiths, joiners, carpenters, electricians – who had the task of transforming one of the houses inul. Garibaldiego into a large warehouse.

The warehouse was divided into separate sections in which were later sorted clothing, shoes, furniture, lamps, sewing machines and type

writers, electrical appliances, sculptures, valuables and the like. This warehouse must have been huge as it was intended to contain the belongings of almost 50,000 people. The Germans also organised, from amongst the Jews, special groups called packers”. In the company of several German soldiers, each group drove through the streets of the former ghetto and loaded into the cars everything that had value which was found in the empty apartments.

The German soldiers’ other occupation was searching for Jews who were still hiding in the area of the old Big Ghetto. The city authorities – both civil and military – were aware that there were still many of them. The search for these Jews lasted practically the entire period during which the deportations occurred. The empty quarter was controlled by special patrols, after which they joined the next operation. In the initial period, soldiers of the Black Battalion” joined the Germans – later, the Germans did this alone.

(ul. Strażacka)

In the period after 7th October 1942, this task became easier. In the quiet, which prevailed in the houses and on the streets, it was easier to hear noises, rustlings, the cry of a child or coughing. Specially training dogs assisted the Germans in their task. They could sense a person hiding in a cellar, in an attic and even those hidden between double walls.

The majority of these people were discovered and shot on-the-spot or at the cemetery on ul. Kawia. There were also cases when the Germans were told about those hiding by other Jews who gave this information out of fear or under torture – or for the promise to allow the informer or his family to live.

Some hiding places had been prepared over several months, some had food stored within them to last up to two years and had access to running water. Unfortunately, the majority of these were discovered and the people who hid there were shot or deported to Treblinka.

The area of the Small Ghetto operated as a forced labour camp. Its inhabitants were subjected to life in barracks. Daily, columns of labourers proceded, under guard, to plants which lay outside the ghetto. A section of the Jews also worked in countless craftsmen’s workshops within the ghetto. The workers were not paid. For their labour, they received food ration cards – all numerically marked. Work commenced at 6.00am and was finished by 6.00pm.

V. The Final Liquidation

In January 1943, the Germans conducted further selections in the area of the Small Ghetto. The first of these took place on 4th January. That day, a police cordon encircled the entire ghetto area. Older people, women and children were principally singled out. The selection took place at the Warsaw Market. Its result was that approximately 350 people were sent to Treblinka, among whom were many children who had previously survived the pogrom in the Big Ghetto. That same day, during the course of the selection, a further 200 people were killed in the ghetto. They were later buried in the cemetery on ul. Kawia.

A further blow befell the inhabitants of the Small Ghetto in March 1943. The Germans advised the Council of Elders to prepare a list of people who had relatives abroad. Whispers spread that such people would be exchanged for Germans held captive in England. A fair number allowed themselves to be duped by this lie. On 20th March, many Jews gathered at the Warsaw Market square, ready for their promised departure. At the same time, the Germans issued an order for all remaining members of the Judenrat, doctors, engineers and the entire Jewish intelligencia to report to the square. When it was realised that this was, in fact, another selection, it was too late to turn back. The Germans had parked trucks on ul. Warsawska and loaded onto them the assembled prisoners. Under escort of armed soldiers, they were transported to the cemetery where a mass execution took place. Approximately 130 people were shot.

The policy of extermination was continued into April. On 23rd April, 25 Jews employed by the Ostbahn were killed. The Germans perpetrated this massacre after discovering a cell of the Jewish underground organisation operating within the station which had intended to carry out acts of sabotage on the trains. In June, bunkers and shelters of Jewish underground organisation members were uncovered in the Small Ghetto. This last discovery hastened the Germans’ liquidation operations in the Small Ghetto.

In the first half of June, approximately 50 people were murdered, including a leader of the Ghetto underground movement – a former Polish Army captain, Dr Adam Wolberg. However, the final tragic act in the ghetto played out during 23rd-26th June 1943. Over that period, cordons of various police formations surrounded the ghetto area.

The action commenced with the liquidation of bunkers belonging to fighters of the Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB). The remaining few thousand ghetto inhabitants were gathered into the parade ground. They stood in the square for six hours waiting for the results of searches which

the Germans had commenced.

Accompanied by dogs, they penetrated underground the ghetto searching for bunkers. This operation was a major surprise for members of ŻOB (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa) such that they could not manage to camouflage the entrances to the bunkers or to hide themselves in time. Already by the ghetto gate, trucks were waiting. The Germans loaded a number of the fighters onto the trucks and into cars which drove off in the direction of the cemetery where they were executed – shot in the back of the head. The trucks made several such trips that day.

This time, the selection was carried differently – victims are not chosen individually, but by columns or rows. Again, the majority are the elderly, women and children. The sick in the hospital are killed where they lie. This “action” finishes in the late afternoon of 25th June. From 8th October 1942 to 25th June 1943, approximately 1,300 Small Ghetto inhabitants are murdered – aound 3,900 people remain alive. On 25th June, the remaining prisoners still standing on the parade ground were divided into smaller groups and transported to several factories in the Częstochowa area or in the vicinity: HASAG-Pelcery, Raków, Częstochowianka, Warta. They were to work there until January 1945 – with the quiet hope of survival.

The action in the Small Ghetto lasted almost a month. On 27th June, units of the army equipped with howitzers encircled the ghetto. Over many hours, shots are fired into the now empty buildings of the former Small Ghetto. The purpose of this was to scare those from the ruins who had, through some miracle, managed to avoid the fate of the others. On the following day, namely 28th June, German cars drive into the Ghetto area.

Through a megaphone, they announced that those who leave their hiding-places voluntarily will receive bread, marmalade and warm soup. They will also be included in an amnesty. The deadline to come forward was set as 30th June.

When the deadline had passed, it turned out that only a few Jews believed the promises of the Germans. On 1st July, soldiers enter the ghetto area covered with the ruins of homes. They find around 20 starving people – mainly elderly, women and children. They are then subjected to many hours’ interrogation, forced to reveal hiding places of other people or of valuables. After the interrogation, they are transported to the cemetery and shot.

Finally, on 20th July, minesweepers and explosives specialists enter the ghetto. Explosive charges are laid beneath houses. After a few hours, the Ghetto in Częstochowa is reduced to piles of rubble.

VI. Judenrat

The Judenrat was appointed on 16th September 1939 and had an identical role to that in other Jewish ghettoes. The Ghetto in Częstochowa was not an exception to the rule, so that the Jewish Council was an involuntary tool in the hands of the Germans. Through the Judenrat, the Germans squeezed high contributions from the Jewish populace. The Council was also obliged to meet quotas from the German authorities to provide workers for forced labour.

Firstly, in Częstochowa, a six-man representation was established for the Jewish population which was later replaced by a 24-man Council. Its Chairman was Leon Kopiński. By November 1939, the German authorities were already demanding of the Jews of Częstochowa contributions as high as 1 million złotych, for which a section of the Council members were detained as hostages. The amount of this contribution was eventually reduced to 400,000 złotych which could be paid off in instalments.

Over time, various offices were established within the Judenrat – commissions and departments such as the Labour Office, the Housing Office, the Requisitions Office, etc. The Council was composed of, among others, lawyers J.Gitler, Z.Rotbart and S.Pohorille; former athlete Bernard Kurland (as head of the Labour Office); former rector of the Jewish Gimnazjum Anisfelt (responsible for education); Kohlenbrenner (boss of the Housing Commission) as well as L. Bromberg and N. D .Berliner.

The Judenrat members, under the leadership of Kopiński, managed the ghetto day-to-day based upon German orders and regulations. They organised quotas of workers for forced labour, allocated newly-arrived Jews to apartments, collected contributions and provided meals for the poor and homeless. In 1942, when rumours spread through the Ghetto of proposed deportations, Council members travelled to Kraków and met with Hans Frank, delivering him a donation of 100,000 złotych in order to gain from him an assurance that no special operation was being prepared against the Jews of Częstochowa.

The Judenrat ceased to exist, in practical terms, in October 1942 following the liquidation of the Big Ghetto. Council members were among the last to be transported to Treblinka along with the entire Jewish Police. Council Chairman, Leon Kopiński, was shot on-the-spot on the charge of being disloyal to the German authorities. The only one who remained and who managed to live for a few more months was Bernard Kurland.

The Jewish Council was also responsible for the Jewish police in the ghetto. At its maximum in 1942, the Jewish Police numbered aound 250 people. Its first Commanding Officer was Maurycy Galster, but he was removed by the Germans after a short time. The task of organising the police fell to Anisfelt. He interviewed candidates with the aid of two other brigade members , and sometimes with the support of Kurland and Kopiński. The second Commanding Officer of police was a man by the name of Parasol – a former non-commissioned officer in the Polish army. Auerbach, a former Polish army officer and a certain lawyer became his closest associates.

Sources:

Text Author:

Radosław Butryński

His website is:

www.dws-xip.pl

We thank him sincerely

for his kind permission to

to reproduce his article here.

(The original text was translated

into English by Andrew Rajcher)

Photographs:

Many of the photographs

on this page come from a

discarded album found, in

Regensberg in 1945, by an

American soldier who was

serving in Company B, of the

56th Armoured Engineer

Battalion. The album had

belonged to a German soldier.

The album and its contants

were donated to the United

States Holocaust Memorial

Museum in Washington DC.

Our thanks to Dotty Grimes,

that US soldier’s daughter,

for this information.