The "Old Synagogue"

The "Old Synagogue"

Background

The earliest evidence of the presence of Jews in Częstochowa dates back to the 17th Century and is found in the reports of the royal inspections from the years 1620 and 1631.

The earliest evidence of the presence of Jews in Częstochowa dates back to the 17th Century and is found in the reports of the royal inspections from the years 1620 and 1631.

A separate Jewish Religious Community was established in 1808, when the Calisian Department gave its permission to create the community in Old Częstochowa.

The exact date of the start of the construction of the Old Synagogue (Stara Synagoga) at ul Nadrzeczna 32 is unknown. The building was expanded in 1872 and then renovated in 1928-29.

It was ransacked by the Germans in September 1939, who then competely destroyed it during the liquidation of the Small Ghetto in 1943.

The Artist

At the instigation of Harav Reb Nachum Asz – Częstochowa’s Chief Rabbi, Professor Perec Willenberg designed the new ornate interior for the renovation of the Old Synagogue which, sadly, only lasted a few years until the building was destroyed by the Nazis.

Professor Willenberg, a graduate of the Fine Arts Academy, taught art and painting in the established Jewish schools, as well as in the artistic school that he founded.

He designed beautiful polychromes and stained glass windows for synagogues in Częstochowa, Piotrków Trybunalski and Opatów.

During the war, he hid in Warsaw under the name of Karol Baltazar Pękosławski. He died in 1947.

His son, Samuel Willenberg z”l, a survivor of the Treblinka death camp uprising, lived in Tel Aviv and was a noted sculptor and artist in his own right.

Beauty Lost Forever

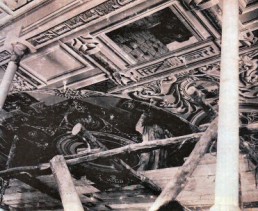

Like a latter day Michaelangelo,

Professor Perec Willenberg

lovingly works on the ceiling

of the Old Synagogue.

His paintings adorned

both the ceiling and the walls

of the Old Synagogue.

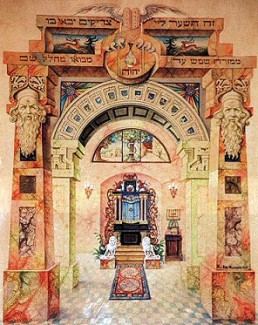

An illustration by

Professor Perec Willenberg

of his design

for the interior

of the Old Synagogue.

The Jews of Częstochowa

The Jews of Częstochowa

- a short history

One of Poland’s largest and most vibrant Jewish communities lived in Częstochowa up until the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the ensuing Holocaust.

Poland’s largest and most vibrant Jewish communities lived in Częstochowa up until the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the ensuing Holocaust.

From the 18th century, followers of traditional Judaism, Hasidic Jews, Reform Jews, Catholics and Protestants lived together in relative peace. Until its devastation, Częstochowa Jewry was famous for its business, cultural, social, and patriotic activities. The city was also renowned for its religious faith and scientific advances. The massive deportations of the Częstochowa Jews to the Treblinka death camp, in September and October 1942, took a toll of 40,000 victims.

The Beginnings

The earliest evidence for the presence of Jews in Częstochowa is found in the reports of royal inspections from the years 1620 and 1631. A few decades later, in 1705, the Council of the City of His Royal Highness took a loan from Mosiek, a Jew, in order to pay a tribute imposed on the city of Częstochowa by the Swedes. In return, Mosiek was allowed to reside in Old Częstochowa until the city had repaid its debt to him.

Częstochowa was also a hotbed of Frankist activity. The founder of this heretical messianic sect, Jacob Frank (1726-1791), was excommunicated by the Jews and sought protection from the Church. He later found himself in dispute with the ecclesiastical authorities and was pressured into converting to Catholicism. He then came into conflict with the Church and was imprisoned in the Jasna Góra fortress. Later, he was freed by the invading Russians.

The stormy days of the Bar Confederation, and the two sieges of Jasna Góra by the Russian army, were not conducive to forming an organised Jewish community. How many Jews lived in Częstochowa until the middle of the 18th century remains obscure. We know that there were 75 Jews in 1765. According to certain sources, a synagogue existed at that time at the intersection of ul. Nadrzeczna and ul. Mirowska. Other sources associate the first house of prayer with the period of the Prussian Partition.

In 1798, Częstochowa Jews decided to separate from the community in nearby Janów. At that time, they established a mikveh (ritual bath house) and a temporary synagogue, probably in the Berman house at Stary Rynek 15. Between the World War I and II, the Chief Rabbi of Częstochowa, Rabbi Nahum Asz, initiated the construction of a larger and richly decorated bath house on grounds belonging to the Jewish Community, at ul. Garibaldiego 18.

When the Jews separated from the Janów community to for a community of their own, the necessity arose for them to establish their own cemetery. Official permission was obtained in 1798. However, the cemetery did not come into being until a year later, because no Catholic would sell the Jews a plot for this purpose. The first funeral – of Izaak, son of Moszek – took place in 1800. For over two years, the tomb was guarded for fear of it being desecrated.

The 19th Century

In 1805, the Częstochowa Jews were granted an official construction permit to erect a synagogue. Three years later, during the period of the Duchy of Warsaw, they were allowed to establish a separate Jewish Community Council. Among other activities, the Community Council maintained its offices, the synagogue, the cemetery, and the mikveh. It supervised ritual slaughter, arranged for social welfare and collected taxes. Initially, only 495 individuals were allowed to belong to the community, although the Jewish population far exceeded that number. At the time, there were 3,349 residents in the growing city.

In the 19th century, when Częstochowa was part of the Russian Partition, the Jews had to struggle in order to maintain their identity. They boycotted the order of Tsar Nicholas I, in 1825, for all Russian citizens to abandon their national costumes and to dress like Europeans. Policemen equipped with scissors stopped Jews in the streets and would cut their beards, sidelocks and gaberdines. Wigs worn by Jewish women were stripped off. One Saturday, when several police officers stood in front of the synagogue to examine the appearance of the worshippers, the Jews remained in the house of prayer until late in the night.

Another source of conflict with the authorities was the Tsar’s order to provide the names to all the citizens of the Russian Empire. The Jews, despite administrative pressure, would not respect this order. Consequently, the municipality – in a high-handed manner – forced surnames on all the Jews in 1824. As a result, there were 31 Berman’s, 29 Haiman’s, and 28 Landau’s living in Częstochowa at that time. In many cases, they were not related.

In the 19th century, Częstochowa was transformed into an important diverse industrial centre, including extractive and metallurgical works and the manufacture of textiles, toys, and devotional articles. In the 1880’s, next to Łódż, Częstochowa was the second largest industrial city of the Russian Partition. It had the country’s third largest population – after Warsaw and Łódż. Later, Częstochowa became one of the most industrialised cities of the independent Poland. In 1925, the city had within it 136 factories, including 17 large textile plants.

In the 19th century, Częstochowa was transformed into an important diverse industrial centre, including extractive and metallurgical works and the manufacture of textiles, toys, and devotional articles. In the 1880’s, next to Łódż, Częstochowa was the second largest industrial city of the Russian Partition. It had the country’s third largest population – after Warsaw and Łódż. Later, Częstochowa became one of the most industrialised cities of the independent Poland. In 1925, the city had within it 136 factories, including 17 large textile plants.

The Częstochowa Jews were not only active in developing local industry, but were frequently among the initiators of the process. In 1828, David Kronenberg, who earlier owned a dozen or so weaving workshops, established the first textile factory of hand-produced goods. Among the biggest factories established by the Jews until the 1850’s were the Warta Factory of Jute Products, owned by Henryk Markusfeld and Szymon Neuman, the Gnaszyńska textile plant, the factory owned by Izydor Singer and Roman and Zygmunt Markowicz, Langhamer’s picture factory and two factories manufacturing spoons owned by Kohn and Landau, the printing house owned by Szymkowski and Oderfeld and the match factory owned by Sperber.

The Jews were unrivalled in the field of toy manufacturing. At the turn of the 19th century, all toy factories (as many as 15 altogether) in Częstochowa had Jewish owners. Business and forwarding enterprises, warehouses, intermediary agencies, etc. of various sizes developed around factories. New lines of business and professions were emerging. Many Jews also held onto their traditional occupations in handicrafts and commerce. Jewish craftsmen established their own guilds, such as those belonging to tinsmiths, roofers, hairdressers, wig-makers, cap-makers, furriers, metalworkers, bakers, confectioners, upholsterers and brush makers. In 1897, the renowned Craft School for Jews was established. It trained skilled workmen, such as carpenters, locksmiths, mechanics, and electricians.

In the middle of the 19th century, mutual relations tightened between Jews and Poles, particularly between Jewish industrialists and the emerging Polish intelligentsia. The Jews and the Poles were connected, thanks to growing business relations and their common engagement in patriotic, scientific, and cultural activities. Daniel Neufeld, founder and headmaster of the Jewish grammar school (where the language of instruction was Polish), organised patriotic events prior to the January Rising, and was an outstanding advocate of Jewish-Polish rapprochement. Despite sever repression, Częstochowa Jews took part in all the struggles for the independence of Poland. After the 8th September Uprising in 1862, tsarist troops attacked the Old Town inhabited by Jews. Many Jewish homes were set on fire and there were many casualties.

In the last decades of the 19th century, only poor Jews remained in the Old Town, inhabiting tenement houses on ulicy Targowa, Garncarska, Nadrzeczna, Senatorska, Kozia, Gęsia, Ptasia, Mostowa and Spadek. Wealthy people abandoned the confined area of the Jewish quarter and moved to the city centre. Roomy, large-style apartment houses were erected along the I Aleja Najświętszej Marii Panny, on ul. Aleksandrowska (now ul. Wilsona), as well as ul. Odjazdowa (now ul. Piłsudskiego).

Wealthy, open-minded Jews built the so-called New Synagogue on ul. Aleksandrowska. In accordance with the ideals of Haskalah or “Jewish Enlightenment”, they sought to combine secular knowledge with religion. They chose outstanding scientists and scholars to be their religious leaders, such as the historian Mayer Bałaban. Cantor Abraham Birnbaum founded the renowned cantorial school that was attached to the New Synagogue. Its graduates found success and admiration in the United States. He was also the first person to start a Union of Cantors. In his compositions, he combined traditional Jewish themes with the elements of contemporary European music.

Wealthy, open-minded Jews built the so-called New Synagogue on ul. Aleksandrowska. In accordance with the ideals of Haskalah or “Jewish Enlightenment”, they sought to combine secular knowledge with religion. They chose outstanding scientists and scholars to be their religious leaders, such as the historian Mayer Bałaban. Cantor Abraham Birnbaum founded the renowned cantorial school that was attached to the New Synagogue. Its graduates found success and admiration in the United States. He was also the first person to start a Union of Cantors. In his compositions, he combined traditional Jewish themes with the elements of contemporary European music.

The New Synagogue existed for only 46 years. Devastated and robbed of all precious objects, it was set on fire by German military policemen and their Volksdeutche henchmen on Christmas Day, 1939. The Judaic library with its rich music collection was decimated along with the building. In the 1960’s, a philharmonic hall was built on its ruins.

In an earlier period, Polish Standards, from the Napoleonic era were stored in the Old Synagogue. Soldiers, returning from Russia in 1813, handed them over to the local Jews to be hidden. One of the standards was used as a parochet, or curtain for the Aron Hakodesh, the altar cabinet where Torah scrolls are kept. Afterwards, the standards were taken by the Assimilationist Jews from the New Synagogue. The existence of these precious relics was discovered in 1916, during the First World War, when Russian troops withdrew from Częstochowa.

The 20th Century

After Poland regained its independence in 1918, patriotic celebrations took place in both synagogues on the anniversaries of important events in Polish history. In the 1920’s, Rabbi Nahum Asz (pic right) initiated a thorough renovation of the Old Synagogue. It was carried out according to the design of painter Perec Willenberg, who fashioned magnificent symbolic ornaments. He also painted the Polish coats of arms on its walls. On 25th September 1939, Germans, dressed in their uniforms began to demolish the Old Synagogue. They were joined by Volksdeutche and a local mob. After three days of looting and devastation, only the walls, shattered windows, and broken floors remained.

After Poland regained its independence in 1918, patriotic celebrations took place in both synagogues on the anniversaries of important events in Polish history. In the 1920’s, Rabbi Nahum Asz (pic right) initiated a thorough renovation of the Old Synagogue. It was carried out according to the design of painter Perec Willenberg, who fashioned magnificent symbolic ornaments. He also painted the Polish coats of arms on its walls. On 25th September 1939, Germans, dressed in their uniforms began to demolish the Old Synagogue. They were joined by Volksdeutche and a local mob. After three days of looting and devastation, only the walls, shattered windows, and broken floors remained.

Apart from synagogues, there were many Hassidic shtiblekh in Częstochowa, including four houses of prayer connected with the Tsadik from Góra Kalwaria (the Gere Rebbe).

In keeping with the charitable principles of Judaism, the Częstochowa Jews arranged for care of the sick, the aged, orphans, pregnant women, and others in need. The Dobroczynność (“Charity”) association and the Towarzystwo Dobroczynne dla Żydów (“Charitable Association for Jews”) were the largest and most respected charitable institutions.

Thanks to the philanthropists, a home for the aged, and a day nursery for poor pre-school age children were established along with summer and holiday camps. In 1913, a modern 50-bed hospital was erected on ul. Mirowska. This hospital was open to anybody in Częstochowa without regard to religion.

Thanks to the philanthropists, a home for the aged, and a day nursery for poor pre-school age children were established along with summer and holiday camps. In 1913, a modern 50-bed hospital was erected on ul. Mirowska. This hospital was open to anybody in Częstochowa without regard to religion.

Schooling was also a religious obligation. At first, Jews were educated in the numerous cheder schools (there were 32 cheder schools in 1912) and yeshivas that offered mostly religious education. Before the outbreak of the Second World War, Jewish children attended nine primary, comprehensive and public schools, two secondary schools, a grammar school, and several trade schools. The experimental gardening farm, situated at ul. Rolnicza 89, was a teaching institution of special importance. Here, children and young people were prepared to live and work in Palestine. Instruction was given by the members of WIZO, the International Zionist Women’s Organization.

WIZO was one of the many Zionist organizations active in Częstochowa. From the 1880’s onward, the Zionists argued with the Assimilationists about total polonization. High hopes for harmonious co-existence with the Poles were raised when Poland regained its independence in 1918. Anti-Semitic excesses, however, weakened the position of those who supported assimilation. At the dawn of the Second Republic, on 28th May 1919, a bloody pogrom – with participation of soldiers from General Haller’s Army – took place in Częstochowa. Seven Jews were killed and many were wounded.

Antisemitic aggression among university students increased in the second half of the 1930’s, as the result of the propaganda fuelled by the National Democratic Movement. Antisemitic incidents that took place in Częstochowa in 1937 had wider repercussions. The synagogue was set on fire, and 46 Jewish shops and 21 apartments were demolished. A feeling of danger and uncertainty over the future was growing amongst the Jews.

All important events in politics, culture and sport were reported and discussed in the local Yiddish press. As many as six Jewish daily newspapers, ten weekly magazines and one bi-weekly magazine were published in Częstochowa before 1939. Yiddish was the primary language of most Jews in Poland.

All important events in politics, culture and sport were reported and discussed in the local Yiddish press. As many as six Jewish daily newspapers, ten weekly magazines and one bi-weekly magazine were published in Częstochowa before 1939. Yiddish was the primary language of most Jews in Poland.

The German army seized Częstochowa on Sunday, 3rd September 1939, in the early morning. By noon the next day, they had brutally brought the city into submission. Several hundred people were killed (some sources report one thousand victims) including many Jews. Over the following days, the persecutions continued, and were, in part, specifically directed at the Jewish population.

At the beginning of the occupation, the Germans immediately ordered all Jewish schools closed. Military and police units moved into some school buildings. On orders of the occupation authorities, a Jewish representative Council of Six was established on the 16th September 1939. Later, on 1st October 1939, it was transformed into the Judenrat, or Council of Elders, composed of 24 members.

The task of the Judenrat was to administer the affairs of the Jewish population and to, unconditionally, execute all the orders of the German occupation authorities.

In the face of resistance by the Polish municipality, nearly the entire burden of services on behalf of the German functionaries and administration fell upon the Judenrat. The Council was obliged to prepare fully furnished flats and office premises. By order of the Germans, the Council was also forced to supply manpower free of charge. The Council was compelled to accommodate Jews deported to Częstochowa from Berlin, from other parts of Germany and from the annexed territories. Meanwhile, more and more Jews, displaced or escaping from neighbouring places, were flooding into Częstochowa. From the beginning of the occupation, the Germans took over Jewish enterprises, blocked bank accounts, and robbed Jews of their possessions. There were many murders, beatings and cases of physical and psychological persecution.

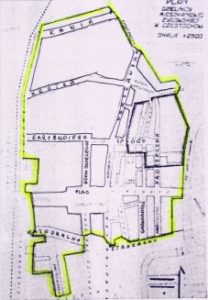

In September 1939, several Jewish political activists were arrested by the Gestapo and deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp. In April 1941, the Germans drove the Jews into the Częstochowa ghetto. Its borders were delimited by the railway line and the wall stretching along the track. German checkpoints were set up on the approach roads to the closed-off area.

In September 1939, several Jewish political activists were arrested by the Gestapo and deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp. In April 1941, the Germans drove the Jews into the Częstochowa ghetto. Its borders were delimited by the railway line and the wall stretching along the track. German checkpoints were set up on the approach roads to the closed-off area.

The Jewish community did not remain passive. In September 1939, the Society for Jewish Population Health Protection (TOZ) continued to function, fixing its attention on malnourished children and youth. Efforts were also made to provide them with education. They also tried to offer medical care to the entire Jewish population.

Various underground military activities and resistance were attempted. However, the deportations of the ghetto residents to Treblinka that began early morning on 22nd September 1942 put a stop to everything. The Germans, with all perfidy and cynicism, chose the most important day on the Jewish calendar – Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) – to liquidate the Częstochowa ghetto. Around 40,000 women, children and men, in five transports, were deported to the gas chambers of Treblinka.

Anyone who offered resistance, along with the weak and the sick, was killed on the spot. Children and pregnant women were marched to ul. Kawia for mass execution. Those murdered were buried in two common graves. At least 2,000 Jews were murdered in Częstochowa at that time alone. Deportations continued until the first days of October. It was at the time of this bloody operation that a Jewish resistance movement began, made up mostly of young people.

During the liquidation of the ghetto, the Germans picked out a group of 856 men and 73 women and transferred them to the HASAG Apparatenbau plant, where wood, distilled-gas generators for trucks were manufactured. An ammunition factory was also set up there. The Częstochowa plant of HASAG (Hugo Schneider Aktiengesellschaft) arms concern was established in the former Pelcera textile factory. Some of the ghetto residents were employed in HASAG Eisenhutte – the former Polish Pelcer’s steel works. Survivors were settled on the premises of other enterprises. The so-called Small Ghetto was established for the Jewish prisoners. 5,185 people including 35 children were placed there. Around 1,500 Jews, together with little children, still remained in hiding. Jewish fighters under Machel Birencwajg’s command smuggled these people into the Small Ghetto, where they had to hide in bunkers and in the attics, since capture meant certain death.

During the liquidation of the ghetto, the Germans picked out a group of 856 men and 73 women and transferred them to the HASAG Apparatenbau plant, where wood, distilled-gas generators for trucks were manufactured. An ammunition factory was also set up there. The Częstochowa plant of HASAG (Hugo Schneider Aktiengesellschaft) arms concern was established in the former Pelcera textile factory. Some of the ghetto residents were employed in HASAG Eisenhutte – the former Polish Pelcer’s steel works. Survivors were settled on the premises of other enterprises. The so-called Small Ghetto was established for the Jewish prisoners. 5,185 people including 35 children were placed there. Around 1,500 Jews, together with little children, still remained in hiding. Jewish fighters under Machel Birencwajg’s command smuggled these people into the Small Ghetto, where they had to hide in bunkers and in the attics, since capture meant certain death.

The liquidation of the Small Ghetto began on Monday morning, 4th January 1943, when the Germans and Ukrainian police surrounded it. Women, children and men were gathered in the Small Marketplace (the Ryneczek), herded onto lorries, and transported to the Jewish cemetery where they were shot. The first act of military resistance was recorded during the selection of Mendel Fiszlewicz, a fugitive from Treblinka and a member of the battle group, and a young woman of unknown identity. They attacked the German officers who were in command of the selection. The action (watched by many people, including a young boy who observed it from hiding) undertaken by these brave young people failed, and they were shot on the spot. In revenge, the Germans shot every fifth person (20 people altogether) among with those who were present in the Ryneczek at that time. All who were killed on that day, later called Bloody Monday, were buried in a common grave.

On the 20th of March 1943, during the so-called Purim Operation, the Germans shot members of the Judenrat, along with their families, in the “kirkut” (the Jewish cemetery).

On the 23rd of March 1943, after a long night of torture, the Germans shot the six fighters who were arrested on the previous day, at 34 Wilsona Street. A grave with the engraved names has remained to this day: Flamenbaum, Moniek -21 years old; Herszenberg, Olek – 25 years old; Krauze, Janek – 23 years old; Rychter, Heniek – 19 years old; Rosenblat, Jerzyk -18 years old; Szajn, Szlamek – 27 years old.

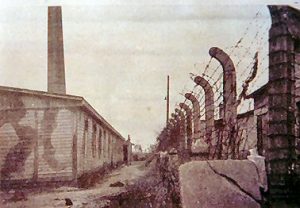

After the liquidation of the Small Ghetto, most of the 4,000 survivors were driven to forced labor camps attached to the HASAG factories. Wooden barracks, surrounded by an electrified, barbed wire fence, were erected on the grounds of the HASAG Apparatenbau. The Jews had to work in the HASAG ammunition factory, where artillery ammunition cases, brought from the front, were reconditioned.

On 20th July 1943, German foremen and the woman-supervisor Koch, notorious for her cruelty, carried out a brutal selection of workers – Jewish men and women and Jewish children from the Kinderkomando. Around 260 people were condemned to death. Several hundred Jews from beyond HASAG were added on the next day. More than 500 people were shot in the Częstochowa Jewish cemetery at that time.

On 20th July 1943, German foremen and the woman-supervisor Koch, notorious for her cruelty, carried out a brutal selection of workers – Jewish men and women and Jewish children from the Kinderkomando. Around 260 people were condemned to death. Several hundred Jews from beyond HASAG were added on the next day. More than 500 people were shot in the Częstochowa Jewish cemetery at that time.

In January 1944, transports of Jews from the Łódź ghetto and the Płaszów camp started to arrive in Częstochowa. More ammunition factories were established. HASAG Częstochowianka and HASAG Warta, as well as new camps for Jews, were attached to them. In July 1944, Jewish prisoners were moved to Częstochowa, together with equipment from HASAG ammunition factories which had been closed down by the Germans in Skarżysko. Eleven thousand Jewish workers were then at work in Częstochowa. On 14th December 1944, the HASAG camps came under the authority of the SS. This resulted in further deterioration of the already inhuman living conditions.

On 15th January 1945, the Germans ordered the evacuation of the HASAG prisoners to the “Reich.” To avoid deportation, individual groups of prisoners, including a large group led by Leon Silberstein, left the camp and awaited liberation. Consequently, the Germans managed to deport only half of the eleven thousand Jews working in the HASAG camps.

Media error: Format(s) not supported or source(s) not found

Download File: https://www.czestochowajews.org/wp-content/uploads/liberation-new.mp4?_=1On the day that Częstochowa was liberated from German occupation, around 5,200 Jews were left in the city, including 1,518 people who had lived in the city before the War (including 1,240 people who had been born there).

The Jews coming from other Polish cities left Częstochowa within three months after liberation. At the same time, 1,195 Hungarian, Czech, Romanian, French, Dutch, Austrian, Yugoslav, and Belgian Jews, and one Jew from Greece, arrived from German territories which had been seized by the Soviet Army. A few weeks later, they, too, left the city.

Rejoicing in the liberation did not last long. Thousands of survivors were homeless and without any means for subsistence. They were without their families and loved ones. Dozens of disabled persons, and hundreds of seriously ill people – people suffering from physical and mental disorders- were in desperate need of help.

Children presente d a particularly serious issue. More than a hundred were orphaned and without protection. The chairman of the Częstochowa Bund organization, Liber Brener, wrote,

d a particularly serious issue. More than a hundred were orphaned and without protection. The chairman of the Częstochowa Bund organization, Liber Brener, wrote,

Children from the camps, children taken back from their Polish protectors, children from the convents, children who survived as herdsmen in the villages and the children wandering through the towns and villages were often in a very bad physical, spiritual and mental shape….

Many children had to be found and then bought back. Many young people were sent to school and an orphanage was set up in the building at ul. Krótka 23, where the Peretz School stood before the War. Sometimes, these orphans were given to substitute families.

Thanks to domestic and foreign financial aid, a rest home for convalescents and the physically exhausted was established near Częstochowa. A Regional Jewish Committee was also organised in Częstochowa. The Committee was composed of representatives from the Bund, the Poale Zion and the PPR. Thanks to support received from the Municipal Housing Commission, most of the Jews in Częstochowa found shelter. Financial help and food was distributed. A common lodging-home for Jews returning from labour camps was set up. The homeless could also find shelter and food there. Shared apartments for young people, as well as a school for children and youth, were established. A health-care institution was also brought into existence. Religious life was reborn after liberation. A room of prayer and a kosher canteen were set up in the mikveh building.

After the War

As the Jewish community began reviving, the tragic events in Kielce and other places in 1946 dramatically changed the situation. In spite of the courageous attitude assumed by Bishop Kubina, the local Jewish community felt threatened again. Jews were given firearms and were stationed at night in front of the orphanage. Surviving Jews began to leave Częstochowa. By August 1956, only about 400 Jews lived in Częstochowa.

In spite of the se events, the Club for Children and Youth was established in the residence of the Markowicz family ul. Jasnogórska 36. The Club was also attended by adults. Activities included courses in Yiddish and Hebrew, amateur theatre, photography, and fine arts. The Club remained active until the antisemitic campaign in 1968, at which time, most of its members dispersed throughout the world.

se events, the Club for Children and Youth was established in the residence of the Markowicz family ul. Jasnogórska 36. The Club was also attended by adults. Activities included courses in Yiddish and Hebrew, amateur theatre, photography, and fine arts. The Club remained active until the antisemitic campaign in 1968, at which time, most of its members dispersed throughout the world.

At the beginning of the 1990’s, the Częstochowa people decided to commemorate the murdered Częstochowa Jews. At the suggestion of Dr.Tadeusz Wrona, the then Mayor of Częstochowa, commemorative plaques in Polish, Hebrew and English, were fixed onto the walls of the Częstochowa Philharmonic Hall, the Zawodzie Hospital, and at ul. Bohaterów Getta (formerly the Ryneczek). At the same time, the Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna (Pedagogical College) in Częstochowa, organised an academic conference. Papers delivered during the Conference were published in the book Dzieje Żydów w Częstochowie” (A History of the Częstochowa Jews), edited by Dr. Zbigniew Jakubowski.

The article on this page

was written by

Prof. Dr. Hab. Jerzy Mizgalski

Historian,

former Vice-Chancellor of the

Jan Długosz University and

one of our Exhibition’s creators.

It originally appeared on the

website of Dr.Mizgalski’s son,

MARCIN MIZGALSKI

and is included within this

website with their

kind permission.