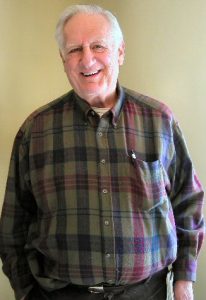

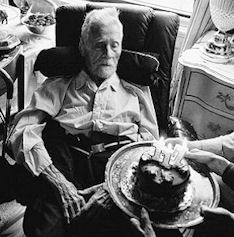

Alvin "Buddy" Rothstein z"l

Alvin "Buddy" Rothstein z"l

How They Got There

How They Got There

He’d been shot down before, so that was nothing new. He’d flown 16 previous missions. And a few weeks before he’d ditched his plane in the North Sea – that was in February of 1945, when hypothermia sets in in 20 minutes.

Now it was March 17th of the same year. And, finding themselves just barely recovering from a flak attack, not knowing whether they were upside down or right side up, Lieutenant Alvin “Buddy” Rothstein of Mountaintop, Pennsylvania, and his co-pilot, Lt. John Bogardus, were lost.

“We were bombing out of England, March 17th, to Ruhland. We ran into flak, anti-aircraft, the electricity was knocked out. Right wheel fuel tank didn’t seal. The hydraulics were out, fear of a spark, lost 10-15 thousand feet. We were in the scud-cloud cover-can’t see wingtips-needle [the magnetic compass], ball and airspeed still working. My co-pilot and I- he was great- got the plane recovered out of a spin, but didn’t know where we were.”

Over their Ruhland [southeast of Dresden] target at 28,000 feet above cloud cover called “scud,” they’d released their bombs when the right wing of the plane was hit by German anti-aircraft fire. The plane had gone into a flat spin and dropped into the scud-visibility zero.

In fact they’d been attacked by German anti-aircraft guns. Four planes were shot down and Buddy and his crew were the only survivors, a nine-man crew. “We were doing strategic bombing over Ruhland-the target might have been an oil field, factories, ball-bearing factories, anything to impede the war effort there.”

It was morning, “very early. We flew from England on ten-twelve hour missions-these were listed on a board at the briefing. A bomb group had four squadrons each with 12-13 planes. Each plane had an 8 or 9-man crew, 25 bomb groups in a formation, like a bomber stream, one bomb group after another over the target.

“The British flew at night. Going over you’d see the British planes coming back, single ships, one at a time. They didn’t want to fly formations at night. Even one at a time it was dangerous. Often a green crew came in and both planes went down. Collision. No survivors. We flew three, four days in a row. One day’s flying was a mission 10 or 12 hours long.”

So here they were, hearing “kerchunk, kerchunk,” as flak tore through the plane. The intercom was dead. They were still airborne, barely under control but had no idea of crew casualties or damage to other planes. As it turned out, a white-hot piece of flak had torn a hole in Sgt. George Livers’ shoe and sock, scorching his ankle. Sgt. Joe Brown’s wrist was scorched by a piece of shrapnel tearing through a metal table his hands were resting on. And damage to the plane was severe.

Lt. Rothstein realized they could never make it back across Germany, the Western Front, and the North Sea, to England. The navigator had brought maps of Germany, France, Holland, not of Poland or Czechoslovakia. Their only hope, risky at best, was to keep the plane airborne, fly east, and hope to reach the Russian-occupied zone. They flew on three engines, with only the magnetic compass working – no hydraulics, none of the cockpit indicator lights or gauges functioning; the gyro-compass had tumbled. Nonetheless they got ready to make an emergency landing, with no real idea where they might be coming down.

“At least we were in the East, behind the Russian lines. I started letting the plane down slowly. We could have run into a mountain. We couldn’t see. But through a break in the cloud we saw a city in the distance. It was early afternoon, 1:30-2:00 pm.

“We see a small grassy field, small planes. What is it? What is the city? Russian reconnaissance and fighter planes were parked. We were trying to get our landing gear down, cranking by hand, hoping to get close to the edge of the field.”

They didn’t know how much fuel they had left, only that when it was gone the plane would go down under little or no control. The precarious landing meant that while Rothstein circled the field, Lt. Bogardus worked the wobble pump next to his seat to provide emergency hydraulic pressure to the landing gear and the braking system. Engineer and Top Gunner Leroy Genoway was lowered by his wrists to make sure the landing gear was locked, and only then could Rothstein touch down as close to the end of the field as possible and immediately drop the tail so that tail drag would act as a brake.

As soon as he thought it safe, Lt. Rothstein stood on the brake pedals-they worked. The B-17 rolled along the short grass field, rapidly approaching a stone wall. Rothstein released the right brake pedal, the plane spun left and stopped.

Parked on the field were several small aircraft which Rothstein hoped were Soviet planes, and they were – small Soviet artillery spotters and some fighter planes, one of whose pilots the crew would soon meet.

Welcome to the Soviet Zone

“The war had taken a turn,” recalled Rothstein. The Russians and Americans, so recently Allies, were mutually suspicious. The Russians had reportedly encountered Germans in American planes, wearing American uniforms, so they were understandably wary. “The Russians,” Rothstein said, “were taking no prisoners, killing American flying crews. We decided to leave our pistols on the plane.” Warily the men descended from their airplane.

“We’re immediately surrounded-bayonets, burp guns [machine guns].” Rothstein, the Captain, salutes the man in charge and offers the only Russian he knows: ‘Ya vas drug, ya Amerikans. Speak English?’

“‘Nyet.’

“‘Parlez Francais?’

“‘Non Nyet.’

“I didn’t want to speak German and get shot, so I took a long shot. ‘Redden Sie Yiddish?’

“The guy says, ‘Du bist a Yid?’

“Turned out he was Officer in Charge, a Jew from Odessa, Boris Petrovich Kasig, a Russian fighter pilot,. saved our lives.”

Rothstein and his crew learned later, mostly by means of sign language, that the unit surrounding his plane had been ordered to shoot all captured prisoners. Because of Lt. Kasig the order was quashed.

Częstochowa

They were in fact in the Russian zone, and the now-nearby city they’d seen in the distance as they approached was Częstochowa, Poland, two months after its liberation from the Germans.

“The little village where the Russian military hosted us was 16 kilometers from Częstochowa.”

Since Lieutenant Kasig still didn’t know when the fliers would be repatriated, they had much time on their hands.

“One day we all walked into the city. There seemed to be very little war damage. The mayor offered us a house to live in, but since we were military we felt we should stay where we were. We attracted a huge crowd, people shouting ‘I have sister Chicago, ‘I have cousin Detroit.’

“The Poles hated the Russians. Their history hasn’t been that great. The Ghetto. The Warsaw Uprising. The word was out the Americans were here to liberate them from the Russians (all nine of us).

“Paul Dempsey, the nose gunner, had Bugs Bunny painted on the back of his jacket. Wherever we went, ‘Micky Mouse! Micky Mouse!” The friendly crowd grew larger and larger, soon pressing in closer and closer, backing them finally into a wall. “Mounted police had to disperse them to allow us to walk through the city.

“They took us on a tour.A priest gave us a special tour of the monastery (Jasna Góra, shrine of the Black Madonna), and told us about the abuse they suffered during the German occupation. They plundered, they stole all the valuable art objects that were hidden away. It was heartbreaking what the Germans and Russians had done.” The airfield where Rothstein and his crew had landed had previously been used by the Luftwaffe. The Russians had removed the mines they’d left when they retreated from the area.

The Americans were escorted to the Hotel Europa, the front doors were locked from the inside, and the police dispersed the crowd outside again. Into the lobby came a Soviet officer. Lt. Rothstein saluted him and was in return saluted. Understanding that they were Americans, the Russian took Rothstein by the arm and escorted him and his crew into the dining room where they joined other Russians.

The Soviet officer ordered meals for everyone-“with the usual, black bread, garlic pickles, potatoes and vodka.” Before the Americans had quite finished, the Russians took their leave. French leave, as it turned out-the bill had not been paid. Rothstein tried as best he could to explain to the hotel manager that none of the Americans had money of any kind. He seemed to understand, and the American crew walked back to their village.

“Another day, a few officers took a young chick and me into the city in a long touring car. They treated me to a Russian style haircut, but were dismayed when I refused to allow them to replace my chipped front tooth and the one next to it with two shiny stainless steel ones. Apparently that was the plan.

“Częstochowa looked like a busy place. I remember seeing a glass sign on a door: ‘Goldberg.’ I got excited. Knocked. Man answered. ‘Goldberg?’ I asked. Shook his head. Like everything else, they took over.”

Rothstein found no Jewish presence in Częstochowa on that visit, although there were probably around 5,000 Jewish survivors there at that time. It was two months after the liberation by the Russians, and a year before the Kielce pogrom.

In the meantime, back in England, Buddy and his crew had been declared Missing In Action.

“For a few weeks we lived with the Russians. They moved a family out of a small house outside the village, and we used the public bath.” The house had a hand-pump. Nuns from the local Roman Catholic church did their laundry, only asking that they be allowed to keep half the soap.

Boris Petrovitch Kasig checked on them everyday.

“‘What do you hear?’ Buddy would ask him.

“‘Alvin, Moscva gavrit nyet – Moscow says nothing.'”

Passover in Ukraine

After more than a week as guests of the Russians, the Americans learned that an American Air Force DC-3 had landed at the airfield. They boarded and were told by the pilot that they would take off as soon as a truck from a nearby village, carrying a downed American B-24 crew, arrived.

After more than a week as guests of the Russians, the Americans learned that an American Air Force DC-3 had landed at the airfield. They boarded and were told by the pilot that they would take off as soon as a truck from a nearby village, carrying a downed American B-24 crew, arrived.

Rothstein had heard about “Special Operation,” under the command of Otto Skorzeny, through which English-speaking German troops were causing havoc behind the Western Front. Fearing a similar trick, and a one-way flight to Siberia, Rothstein questioned the pilot to make sure he was really American and not an English-speaking Soviet officer. He was indeed an American, from Buffalo, and the plane took off for the joint Soviet-American base at Poltava in Ukraine.

As they were landing, Rothstein looked down at the airfield and thought it looked like a junkyard, it was littered with so many aircraft. “They were not in great shape.” Many wrecked aircraft strewed the ground, Soviet and American, bombers and fighter planes.

“Poltava was a creative idea, but brief. The Allies used it for shuttle bombing. Drop their bombs in Germany, go to Poltava, fuel up and get bombs and bomb the Germans on their way back to England.

“So once the Germans followed them. Stukas. German dive bombers leveled the place.”

But while Buddy and his crew were there, they had a far happier experience. At Poltava there was a meteorological centre run by a Major Marvin Rubin, and two small hospitals manned by American doctors, where Rothstein was treated for deteriorating skin conditions and Sgt. Joe Brown was treated for a near-fatal case of dysentery.

“There was a rough rustic building where they handed out clothes.” The officer in charge was Sgt. Rubinoff. When he gave clothes to Lieutenant Rothstein, he asked him, “‘Do you have any other Jewish boys? We have eight here.” Two Jewish guys named Abramowitz and Brown were part of Rothstein’s crew, so there were three more Americans.

“Seder in two days,” Rubinoff said.

Some of the American Jewish men at the base had managed to requisition the necessary food. The Russian cook at the base was Jewish and was more than glad to prepare the dinner.

And Seder there was, in a bombed-out building, with matzos flown in, “pesadiche cake, catered by a Jewish guy in the Russian army. He’d been a caterer in civilian life. He’d bring in the food and leave. He was not allowed by the Soviets to stay.” Nor were other Jewish guards at the base.

Buddy paused for a moment. “I can’t go to or have a Passover Seder,” he said, “without knowing what freedom really is. So if I seem happy, I am.”

From Poltava, Rothstein and his crew were flown back to England via Teheran, Cairo, Athens, Naples, and Marseilles.

Going Home

When the American crew returned to England, “they thought we were dead. They took us to the Dead Man’s Room where they had all your stuff to send back to the ‘next of kin'”

He mused about the aftermath of the war. “There are four of us left from the crew. We were never able to find Joe Brown, the radio operator. He was from Scranton. His wife and my wife were in Brownies and Girl Scouts together. Almost a fluke he ended up on my crew.

“I came back to the States after Germany surrendered, and I was classified to go over to the Pacific to learn to fly B-29’s. Beulah and I decided to get married. We were on our honeymoon when Japan surrendered.” Abramowitz survived the war. He was from New York, but it’s not known where he lives now.

“There was a point system. You enlisted for the duration plus six months. But with enough points you could get out. I was not a military man. I enlisted because there was a war, a bad war.”

How He Got His Start

In fact Rothstein had first worked in a defense plant, Westinghouse, making turbines for the Navy, and was draft exempt.

As the war got hotter, he wanted to go. “I was twenty, twenty-one years old. I had two six-month deferments, then three six-month deferments. After seeing too many war movies, a lot of anti-semitism, I decided that’s really where I belong, and I was fortunate enough to get started and complete pilot training.”

After arduous training he graduated a Second Lieutenant from the Blytheville, Arkansas, airfield. He wanted to go into the Air Force, the Army Air Corps as it then was, and had crammed for the entrance exams and passed.

“I had total confidence that no one was getting better training than I. I was always a very physical guy, played varsity football in high school. And when I got into combat I didn’t choke.

I marvel at what they did. The pressure was great. More intense in each place until the four-engine bomber, bigger than a house. I thought, I’ll never ever learn how to fly this. That was good later on.”

It was in Jackson, Tennessee, early on in in primary flying school and ground school classes that he learned something that saved their lives over Częstochowa.

“I flew a Stearman, two-passenger ‘yellow peril’ for the Navy, very maneuverable, learned how to recover in a spin. Very uncomfortable. You’re looking down but it’s sky. You look up and it’s earth. They teach you how to recover the plane, recover your senses and do it in a hurry.

“In combat you’re in all kinds of different circumstances-plane shot out under you, engines out.”

At the end of Mission 17, Buddy and his crew were able to land near Częstochowa precisely because of their extensive training in coming out of spins, flying through soup. But that was to be his last mission.

A Full Life and a Happy Coincidence

“I ended up being the father of four children, six grandchildren, married 59 years, a builder, developer, in real estate. A full, rich, happy life.”

One of the happy coincidences of that life was an unexpected reconnection with Boris Petrovitch Kasig, the Odessa Jew who saved their lives in the Soviet zone in Poland in 1945.

“My son Dan practiced law for nine years in Moscow, is fluent in five languages. There was a charismatic leader of the Jewish community, Colonel Goichberg.

“Dan said to him, ‘What can I do to help?’

“‘We’d love to teach people Hebrew,’ Goichberg said, ‘but the Russians won’t let us, but maybe you could.’

I Am Boris Petrovitch

“Dan set up two classes, beginning and advanced. Then he told the man he ‘wanted to set up something for my father. He wanted to find Boris Petrovitch Kasig.

‘The guy said, ‘That’s not a Jewish name. There can’t be such a person.’ There was a small Jewish newspaper there, four, five pages. In a few weeks they put in a story about him with Dan’s law office phone number. It had big circulation, that paper.

“A few weeks later a phone call came: ‘I am Boris Petrovitch, and I’ll remember that day as long as I live.’ Boris told Dan to ask his dad about ‘the secret word – laughing-hyena.'”

It turned out “laughing-hyena” was the punch line to a joke.

“Dan flew to Yalta, 1,200 miles away. He met Boris, such a wonderful guy, sweet, warm guy. He wanted to get a job after the war. The answer was, No – you’re a Jew. He married a Russian woman whose father was an Orthodox priest, killed by the Russians. They had two kids. He spent two days with them. Later on they kept in touch. Got stuff weekly to them with the firm’s courier.”

Buddy and Beulah Rothstein had made plans to meet Boris and his family, but “Boris died before we got to see him.”

More Recently

Far from living in the past, however, Buddy has long been active in Rotary International, making friends the Rothsteins are still in touch with.

Far from living in the past, however, Buddy has long been active in Rotary International, making friends the Rothsteins are still in touch with.

“We spent three weeks in Tamil India and three weeks in Sri Lanka, and we’re in touch with people there. We were team leaders for a Rotary program. Studied the factories and farms, learned how they did business, exchanged ideas, and they sent a team over here for six weeks. In a letter dated December 9th, 2004, one of the daughters writes, ‘Dear Auntie Beulah and Uncle Buddy'” with news that though the Rothsteins had stayed with them in Gall Seaport, they now live in Colombo and so escaped the horrors of the tsunami. The daughter is now a medical doctor, her brother an engineer studying aeronautical engineering in Wichita.

“I contacted the district governor in Rotary there,” Buddy said, “to see he has help and so on. The parents were in Colombo when the tsunami hit.”

On September 25, 1997, The Honorable Paul E. Kanjorski delivered a tribute to Buddy Rothstein in the House of Representatives, in connection with Rothstein’s being honoured by the Ethics Institute of Northeastern Pennsylvania. He mentions Rothstein’s military service and his realty company, Rothstein Inc. and Rothstein Construction, Inc., his presidency of Wilkes-Barre Rotary, his service to B’nai B’rith in housing for the elderly, as well as service to the Economic Development Council of Northeastern Pennsylvania.

A second-generation American, Buddy Rothstein, born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, indeed had a full rich life.

[Webmaster: Sadly, Buddy passed away, at the age on 90, on 25th January 2012 in Wilkes-Barre.]

Submitted by:

Iris Rosencwajg

Iris, who teaches English at Houston Community College’s central campus, is a second generation survivor and serves on the Holocaust Museum Houston’s Academic Committee. Her father emigrated from Częstochowa to Houston.

She based this article on interviews with Buddy Rothstein and on various newspaper articles,

including one written by Ray Saul, in the Hazelton, Pennsylvania “Standard-Speaker”.

Bolesława Proskurowska z"l

Bolesława Proskurowska z"l

We stand before the remains of Bolesława, of blessed memory. In a moment, her body will have eternal rest in mother-earth. Deep in mourning, in silence and profound thought, we bow our heads not only over remains of the deceased. We also bow our heads over the remains of the generation which experienced the greatest tragedy of the Jewish people in modern history.

before the remains of Bolesława, of blessed memory. In a moment, her body will have eternal rest in mother-earth. Deep in mourning, in silence and profound thought, we bow our heads not only over remains of the deceased. We also bow our heads over the remains of the generation which experienced the greatest tragedy of the Jewish people in modern history.

The life of Bolesława was a living tableau of the tragedy of our people – a people who, for over three centuries, has lived in Częstochowa. Amongst our small group of Częstochowa Jews, Bolesława was a determined bridge between the present day and a world which has irrevocably departed.

With pride, Bolesława always stressed her own origins. She was, at the same time, a patriot of her city from which, despite various opportunities, she did not wish to leave.

Always with a sense of humour, she vividly remembered her own childhood and her younger years. For hours on end, she would speak with the young people of the Słowacki Lyceum (from which she, herself, was a graduate), about pre-War Częstochowa, about the tragedy of the ghetto and of the Holocaust. She concerned herself, to the last of her days, with present-day problems. She was a cultured lady often delving into the wealth of Polish and world literature and poetry. She loved being surrounded by a world of people, animals and nature.

With her sunny disposition, with a joke, she could bring to life every meeting, supporting each of us in moments of difficulty. She taught us patience, to draw joy from the smallest things in life, to be proud and to remain in the traditions of our own people. In the blessed Bolesława, we lose a friend and “a member of the family” who was so necessary in our lives, such as we would miss one of our cousins, aunts or uncles.

On behalf of myself and in the name of the whole of our circle of members of the Częstochowa branch of the TSKŻ, we bid farewell to the blessed Bolesława Proskurowska.

The Eulogy at

the funeral of

Bolesława Proskurowska z”l

held on

11th August 2006

delivered by

Halina Wasilewicz z”l

– former Chairperson,

Częstochowa Branch

Social and Cultural

Association of Jews

Translated into

English by

Andrew Rajcher

Esther (Ada) Frajman Ofir z"l

Esther (Ada) Frajman Ofir z"l

- Częstochowa Holocaust Survivor

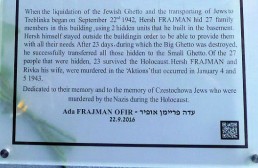

On 22nd September 2016, during our World Society’s Fifth Reunion, a memorial plaque was unveiled at Stary Rynek 24 (Old Market Square) commemorating the site where, seventy four years earlier, Esther’s family and other Jews went into hiding.

On 22nd September 2016, during our World Society’s Fifth Reunion, a memorial plaque was unveiled at Stary Rynek 24 (Old Market Square) commemorating the site where, seventy four years earlier, Esther’s family and other Jews went into hiding.

That was the day when the Nazis began the liquidation of the “Small Ghetto”. The cramped, damp basement of that building became the hiding place for twenty seven Jews, the survival of whom became a mission for Esther’s father.

The memorial plaque (above) was unveiled by Esther in the presence of her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and was covered by the local media. The plaque honours the memory of her parents and the Jews of Częstochowa who perished in the Holocaust.

Thankfully, for posterity, Esther wrote her memoirs entitled, in English, “Thus Began My New Life”, the PDF’s of which are available to read online, by clicking on one of the three links below

Sadly, Esther passed away on 3rd July 2017.

May her memory be a blessing to her family and to all of us.

During our World Society’s Fifth Reunion in 2016, I had the privilege of being Esther’s Polish-to-English interpreter, as she told her amazing story to a lecture hall full of academics, high school students and Reunion participants.

For me, it was a truly amazing experience. As an interpreter, one needs to concentate on what is being said, without becoming emotionally involved in the content. As Esther told her story, and that of her family, for me, this requirement became quite difficult.

It was an experience which I will long remember.

My thanks go to Alon Goldman, Chairman,

Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel,

for providing me with the text of Esther’s memoirs in all three languages.

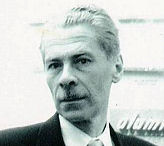

Alexander Imich z"l

Alexander Imich z"l

- in 2014, the oldest man in the world

A lexander Imich was born in Częstochowa on 4th February 1903 into a secular family. His father, who owned a decorating business, installed an airstrip for early aviators. “At the time, flying was a demonstration,” he recalls. “It attracted people for the show.” He called “the aeroplane” the greatest invention of his lifetime. He also remembers Częstochowa’s first automobiles.

lexander Imich was born in Częstochowa on 4th February 1903 into a secular family. His father, who owned a decorating business, installed an airstrip for early aviators. “At the time, flying was a demonstration,” he recalls. “It attracted people for the show.” He called “the aeroplane” the greatest invention of his lifetime. He also remembers Częstochowa’s first automobiles.

He sought to become a captain in the Polish Navy, but as a Jew was told to forget it. “I decided to become a zoologist and travel to exotic countries in Africa,” Alexander recalled. But blocked from advancement, he switched to chemistry, earning a doctorate at Jagiellonian University in Kraków.

On 4th May 1921, he sat for his written matriculation examinations at the Sienkiewicz school, and then, on 5th June 1921 sat for his oral examinations.

In the early 1930’s, Alexander Imich grew fascinated with a Polish medium who was known as “Matylda S.”, a doctor’s widow gaining renown for séances that reportedly called up the dead. He participated in numerous inexplicable encounters that he detailed in a German scholarly journal in 1932 and recounted in an anthology he edited, “Incredible Tales of the Paranormal”, published by Bramble Books in 1995 (at the age of 95!!).

He keeps a box of forks and spoons twisted in macropsychokinesis experiments. “I watched ordinary people doing that,” he said, although he himself was unable to duplicate it.

He married a childhood sweetheart who, a few years later, left him for another man. He then married her friend, Wela. When the Nazis overran Poland in 1939, they fled east to Soviet-occupied Białystok. Refusing to accept Soviet nationality, they were shipped off to a labour camp.

With Russia reeling under German attack, they were freed and moved to Samarkand, in what is now Uzbekistan, and then back to Poland. There they found that many family members had died in the Holocaust. In 1951, they immigrated to Waterbury, Connecticut.

Wela Imich, a painter and psychotherapist, opened a practice in Manhattan. After she died in 1986, Alexander moved into her suite in a pre-War apartment hotel in Manhattan. Eight years later, it was turned into a luxury seniors residence and he was “grandfathered” in. His savings vanished in dubious investments and The New York Times Neediest Cases campaign came to his aid in 2007.

He and his wife never had children. (His closest relative is an 84-year-old nephew.)

He and his wife never had children. (His closest relative is an 84-year-old nephew.)

So what are his secrets of longevity? Did his many hardships prolong his life? “It’s hard to say.” He credited “good genes” and athletics. “I was a gymnast,” he said. “Good runner, a good springer. Good javelin, and I was a good swimmer.” He used to smoke, but gave it up long ago. Alcohol? Never, he said.

He always ate sparingly, inspired by Eastern mystics who disdain food. “There are some people in India who do not eat,” he said admiringly. Now, his home-care aides said that he fancies matzo balls, gefilte fish, chicken noodle soup, Ritz crackers, scrambled eggs, chocolate and ice cream.

(Alexander Imich passed away on Sunday 8th June 2014. He held the title of the world’s oldest man, albeit sadly, for only a short time.)

Sources:

The New York Times

and

Częstochowa biuletyn informacji publicznej.

The Finkelstein Family

The Finkelstein Family

nee Dziubas

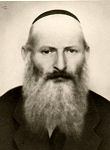

The Dziubas family was very orthodox, Gere Hassidim, and, on ul Nadrzeczna 36-38, they built the biggest soap factory in Poland and Russia.

In 1895, Majtla Dziubas married Abraham Hanoch Finkelstein, who was born in Sosnowiec.

As well as being a Jewish scholar, Abraham was a chemist and worked in his father-in-law’s soap factory, while studying Jewish texts “all day long”.

Between 1896 and 1913, they had eleven children, eight sons and three daughters. Each of them eventually turned away from religion and became a Socialist-Zionist – several were members of Hashomer Hatsair.

Between 1896 and 1913, they had eleven children, eight sons and three daughters. Each of them eventually turned away from religion and became a Socialist-Zionist – several were members of Hashomer Hatsair.

Living by the Warta River, their home was vibrant with a passion for chemistry, music, and tikkun olam. Majtla was such a good mother that each child had the feeling he/she was her favourite.

Living by the Warta River, their home was vibrant with a passion for chemistry, music, and tikkun olam. Majtla was such a good mother that each child had the feeling he/she was her favourite.

The older son, Motel, became a journalist. Because of the numerus clausus, Moshe, Victor and, later, my father Luzer went to France to study.

In 1933, Abraham died of a heart attack.

R egina survived working in Hasag, Cesia and Włodek worked in Germany as Aryan Poles, Luzer> fought with the partisans in Belarus, Perec escaped to Russia.

egina survived working in Hasag, Cesia and Włodek worked in Germany as Aryan Poles, Luzer> fought with the partisans in Belarus, Perec escaped to Russia.

Motel was tortured and murdered in Treblinka. Sala died of typhus in Częstochowa.

My grandmother, Majtla was taken to Treblinka in September 1942. Her grandchildren, who never knew her, are dispersed around the world in Israel, France and the United States.

Sylvie Finkelstein

– granddaughter of

Abraham Hanoch and

Majtla (nee Dziubas) Finkelstein

Felix Beatus z"l

Felix Beatus

Felix Beatus was born in 1917 into an assimilated family in Kalisz. Around 1931, they moved to Częstochowa, where his family ran a paper-bag manufacturing business on ul.Garibaldiego. When War broke out in 1939, with his wife Francesca, he fled with the Polish army retreating into Russia-Ukraine, where he found work near the city of Sitri as a driver. Francesca worked as a nurse.

Felix Beatus was born in 1917 into an assimilated family in Kalisz. Around 1931, they moved to Częstochowa, where his family ran a paper-bag manufacturing business on ul.Garibaldiego. When War broke out in 1939, with his wife Francesca, he fled with the Polish army retreating into Russia-Ukraine, where he found work near the city of Sitri as a driver. Francesca worked as a nurse.

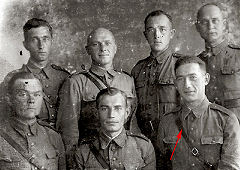

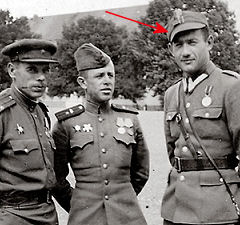

In June 1941, when Germany invaded Russia, Felix’s truck was stopped at a road block. That same night, he was drafted into the Red Army as a truck driver. Felix said to the Russian commander, “Either I’ll be a good soldier or no soldier at all. But you have to let me inform my wife that I’ve been drafted”. The Commander agreed and sent him, with a guard, to tell his wife. The next time he saw his wife was nearly four years later, after the War.

As a driver, Felix’s technical talent was already evident. There were no spare parts but many scrap vehicles were littered along the roads. At the age of 28, he was sent to the Ukrainian front, where he was wounded. When he recovered, he was sent to become a tank soldier in the Polish Army which had been established by the Soviets.

His commanders wanted Felix to become a Politruk (a army political officer), but he refused saying that he did not wish to become a “Politruk Jew among Polish soldiers”. However, his commanders insisted and threw him into prison, Eventually he was released and dispatched to a T-34 tank commanders course.

At the end of the course, in October 1943, Felix was sent to the fight near Warsaw with General Herling. The Poles sent him to an armoured officer’s course in Russia and then on to an advanced armoured reconnaissance course.

In July 1944, Felix’s Polish brigade arrived in Lublin and he was among those who liberated the Majdanek death camp. After Lublin, the great battle to retake Warsaw from the Germans began. Felix was in the intelligence unit’s patrol division which formed the bridgehead on the Wisła River, enabling the first tanks to cross to the other side.

The Warsaw Uprising broke out. The Polish military commanders wanted to join the rebels and to participate in the liberation of Warsaw, but the Russians were apparently more interested in the downfall of the Polish Army. The Uprising failed with thousands of casualties.

Meanwhile, Felix’s commanders decided to send him to the Molotov Academy in Leningrad where, for half a year, he studied advanced armoured warfare. This was vocational training at the highest-level given to commanders of armoured brigades. Study was based on lessons learned from fighting the war, not yet ended. Each participant learned combat planning and practice of a full armoured brigade. Field training sessions were held at brigade level with the help of Finland.

Meanwhile, Felix’s commanders decided to send him to the Molotov Academy in Leningrad where, for half a year, he studied advanced armoured warfare. This was vocational training at the highest-level given to commanders of armoured brigades. Study was based on lessons learned from fighting the war, not yet ended. Each participant learned combat planning and practice of a full armoured brigade. Field training sessions were held at brigade level with the help of Finland.

Following this training, Felix returned to the Wisła front where he commanded a Polish Army armoured battalion comprised of Russian soldiers and tanks. In one of the fiercest battles against the Germans, in April 1945, his force was practically destroyed, leaving him with only seven tanks. Russian reinforcements of Stalin tanks with 122mm guns saved the rest of his unit. In May 1945, he completed his service on the border of the Czech Republic and Germany.

Felix was then called, with his unit, to the city of Stettin, where Germans, Russians and Poles, who returned from captivity, were fighting each other. He received an order from Moscow to clear the city of German residents, and turn it into purely Polish town before the Potsdam Conference (July 1945, the division of spheres of influence in Europe following the fall of Germany). Stettin then became Szczecin.

Within six weeks, Felix had managed to transfer a quarter of a million German inhabitants of Stettin and had become Military Governor of the city. It was here that Felix was first exposed to “Irgun Ha’Bricha”. Under pressure from his wife, he met with members of the Aliyah Bet organisation and helped them to illegally smuggle Holocaust survivors to Palestine.

On 16 April 1946 the Polish Government decided to hold a victory parade in Szczecin and Felix was assigned the task of organising it. Among the guests he invited was a Jewish youth group undergoing agricultural training prior to immigration to Palestine. While heading the parade’s armoured column, he could see Jewish youth marching with both the Polish flag and the blue and white flag. He also saw how they were despised by thousands of the Polish Scouts yelling “Jews to Palestine”. It was apparently then that he came to the decision to immigrate to Israel.

On 27th May 1947, Felix arrived in Palestine with his family. While he was fluent in Polish, Russian and German, he knew not one word of Hebrew. Maccabi Motzri (a senior Haganah and Palmach officer at the time) met him and took him to meet with Yitzhak Sadeh, Yigal Allon and Dan Lehner in a Tel Aviv Cafe. With Yitzhak Sadeh, he spoke Russian, with Dan Lehner, he spoke German. However, Yigal tried to speak to him in Yiddish, a language which Felix did not understand. “How come you are Jewish and don’t understand Yiddish?”, Allon asked him.

On 27th May 1947, Felix arrived in Palestine with his family. While he was fluent in Polish, Russian and German, he knew not one word of Hebrew. Maccabi Motzri (a senior Haganah and Palmach officer at the time) met him and took him to meet with Yitzhak Sadeh, Yigal Allon and Dan Lehner in a Tel Aviv Cafe. With Yitzhak Sadeh, he spoke Russian, with Dan Lehner, he spoke German. However, Yigal tried to speak to him in Yiddish, a language which Felix did not understand. “How come you are Jewish and don’t understand Yiddish?”, Allon asked him.

With an interpreter, Felix was sent first to the Galilee, where Yitzhak Sadeh had asked him to organise the planning of its defence. In Kibbutz Ayelet Hashachar, he met Molah Cohen, commander of the Palmach Third Battalion, who asked him “How long have you been in the country? You seem so familiar with the area!” According to Dan Lehner, “Felix has been here only a few days and knows all the places just from studying the maps”.

Until March 1948, Felix was busy creating an armoured warfare training facility. He had brought with him a great deal of training literature and translated it in the Sarona training camp (now the Ministry of Defence centre in Tel Aviv).

When the fighting began on the roads, he persuaded Yitzhak Sadeh to stop using armoured “sandwich” vehicles with arrow slits, since they were like death traps with limited fire and observation possibilities. Instead, he developed a protected vehicle based on a Dodge truck with a welded steel bottom plate and top turret of steel with the possibility of easy swing and machine gun openings.

Yitzhak Sadeh then called Felix and said to him, “We have some tanks!”

According to Felix, “We came to a large warehouse at the port of Tel Aviv. There were ten Hotchkiss H-35 tanks, each one with a technical problem. This was a French tank, developed after World War I, with a short 37mm cannon. The next day we went to an orchard in Bnei Brak where there were some half-tracks.

“That’s it”, said Yitzhak Sadeh. “Now we can form an armoured battalion.”

“That’s not enough”, replied Felix. “We still need soldiers, mechanics, communications, ammunition and supplies”.

“Look”, said Yitzhak Sadeh. “We have a Commander, that’s you, and we have tanks. As far as the rest is concerned, we’ll manage!”

Felix recalled that “during the first two weeks of April, new immigrants, who previously served in the armoured corps, started arriving from Czechoslovakia and Russia. They began to get organized in Tel-Levinsky, amidst a jumble of languages. I decided to set up three companies: the Slavs would have the Hotchkiss, the Anglo-Saxons would have the Cromwell tanks stolen from the English and the two Sherman tanks assembled from different spare parts, and an Etzel squadron under the command of the Jacob Banai would get the half-tracks”.

With the 8th Brigade, commanded by Yitzhak Sadeh, the first armoured battalion of the IDF (the 82nd) under the command of Felix Beatus, was established in May 1948 and it’s first battle was in Operation Dani, the conquest of Ramle-Lod, the nearby airport and the villages and roads in the area.

Irit Amiel

Irit Amiel

- Poet, Writer Hebrew/Polish Writer and Translator

Irit Amiel, formerly Irena Librowicz, was born on 5th May 1931 in Częstochowa to a modern Jewish family, the daughter of Leon and Yentl (Hasenfeld) Librowicz. Her ancestors came to Poland around 400 years ago.

Irit Amiel, formerly Irena Librowicz, was born on 5th May 1931 in Częstochowa to a modern Jewish family, the daughter of Leon and Yentl (Hasenfeld) Librowicz. Her ancestors came to Poland around 400 years ago.

Duriing the War, she was in the Częstochowa ghetto. Her father managed to have her smuggled out of the ghetto and, with the help of Poles and false documents, she survived the War in hiding in a village and in Warsaw. Sadly, her parents and relatives perished in Treblina.

Together with a group of other young people, she managed to reach Palestine illegally in 1947 where, at first, she settled on a kibbutz. She then studied philology, history and literary history at the Open University of Ra’anana. Her post-graduate education was in Translation Studies at Beit Berl Kfar Saba College.

She made her literary debut in 1994 with a collection of Hebrew poems in a book relating to the Holocaust. A Polish language edition of that book was published in that same year. There then followed other literary works, all of which have also been published in Poland. These include poetry “I Could Not”(1998), “Test in the Holocaust” (1994, 1998), “Here and There” (1999), “Breathe Deeply” (2002), and prose including “Carbonized” (1999), “Dual View” (2008) and “Life – a Temporary Title” (2014). She has been twice nominated for the Nike Literary Prize.

Her works have also been published in English, German, Italian and Hungarian.

She has translated literary works from Polish to Hebrew and vice vera. Among the authors whose works she has translated are Marek Hłasko, Hanna Krall, Henryk Grynberg, Leo Lipski and Lucia Glicksman. into Hebrew.

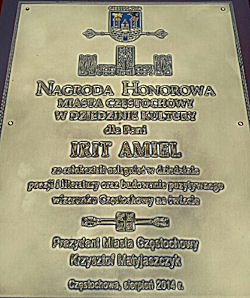

In May 2014, as part of the Aleja … tu się dziejie festival, the City of Częstochowa invited Irit to take part in the event.

She used that opportunity to show her daughter where she had lived, where she had been in the ghetto, and from where she had escaped.

To mark the occasion, the Częstochowa City Council made a video of her visit..

The City of Częstochowa honoured Irit with an Honorary Award for Literary Achievement. Irit accepted the Award, in November 2014, at her home in Israel. It was presented to her by Alon Goldman, World Society Vice-President and Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel.

Webmaster’s Comment:

The contents on this page

has been compiled from material supplied by

Alon Goldman, Chairman of the

Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel

and from material about Irit

which appears on Wikipedia.

Lives & Legends

Write a Tribute

- for the "Lives & Legends" section of our website

their grandparents or other members of their nuclear or extended family,

who either survived or perished in the Holocaust.

- In fact, anyone who wishes to may write a tribute page to some or all of their family,

so long as their family comes from Częstochowa or the surrounding area.

- Each tribute should be a maximum of 1,500 words (in WORD or plain text format)

and MUST be accompanied by at least 2 or up to 4 photographs (a page of plain text

without a pic or two does not look good at all)..

- Each tribute should be headed CLEARLY with the names of the people being written about.

- You may submit a tribute for as many families as you wish – but please,

write each one SEPARATELY.

- Please state clearly the name you want to appear as the author of the tribute and,

optionally, your relationship to the family being written about.

All tributes

should be

emailed to

the Webmaster

at

aragorn@axiomcs.com.au

Sigi z"l & Hanka Siegreich

Sigi z"l & Hanka Siegreich

- a love story: Częstochowa Holocaust survivors celebrating seven decades of marriage

Melbourne Australia couple Sigi (93) and Hanka (91) say after all of these years they are still very much in love.

Melbourne Australia couple Sigi (93) and Hanka (91) say after all of these years they are still very much in love.

Having virtually grown up in labour camps, the teenagers were both wasting away when their eyes first locked in the Częstochowa camp in Poland.

“I lost my mind,” Sigi says. “When I saw her, the whole world was turning around me. I saw a pair of beautiful eyes and I heard bells ringing.”

It was New Year’s Eve 1944, eighteen days before the camp was liberated by the Red Army.

“I had no interest in girls, because I was a skeleton,” Sigi says. “There was a pair of beautiful eyes looking at me, with a smile like I never saw in my life.”

He approached her and they talked. Before returning to his barracks he gave her a kiss on the cheek.

“I remember the first kiss,” Hanka says as she puts her hand on her face. That is exactly what she did on that first day because, she says, she wanted to hold onto it forever. Sigi had stood out in an environment where the inhumane conditions had left most people shells of their former selves.

“At that time, the people in the camp were terrible,” she says. “He was very gentle.”

Over the coming days, this new love was tested. Sigi had been working in the munitions workshop making bullets for the Nazi German army. He says he had been sabotaging the factory line making bullets too small for the gun barrels. When he received word that the Gestapo were looking for him, he found a hiding spot in a nearby abandoned construction site. He says only Hanka knew where he was hiding.

“She was the only person I could trust my life with,” he says.

Hanka says she risked her life to keep him alive smuggling him small pieces of her bread ration and a blanket that she had made to keep him warm on -15 degree nights. Then one night, she came for a second visit. This time, she was smiling and had her arms out. The camp was being liberated.

“They’re gone,” she told him. “We are free.”

The next day they were married.

The year after, Hanka gave birth to the first of their two daughters, Evelyne, the first baby born to Holocaust survivors in Sigi’s home town of Katowice after the war.

Sigi and friend Adam Frydman, a fellow camp inmate and witness to his marriage to Hanka.

Sigi and friend Adam Frydman, a fellow camp inmate and witness to his marriage to Hanka.

Sigi and Hanka Siegreich with

Sigi and Hanka Siegreich with

their daughter Evelyne in 1946.

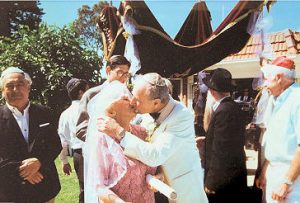

Having moved to Australia in 1971, it wasn’t until their 50th wedding anniversary that the couple had a proper wedding, in their daughter’s Melbourne backyard.

Having moved to Australia in 1971, it wasn’t until their 50th wedding anniversary that the couple had a proper wedding, in their daughter’s Melbourne backyard.

Amazingly, their witnesses were fellow inmates at the labour camp, who had also witnessed their 1945 marriage signing.

“We’ve achieved a lot,” Sigi says. “We’ve got so many grandchildren and great grandchildren. She charmed me. That was that, the rest was history.”

Unlike Hanka and Sigi, only a handful of their classmates survived the Holocaust. Their great-grandson’s school, Bialik College, is currently collecting 1.5 million buttons to honour the children who were murdered under the Nazi regime. Sigi is donating 180 buttons to the project this month, to represent the family he lost in the Holocaust.

The doting couple, aged 93 and 91, have already had their gravestones prepared, side by side, for when they leave this world. The inscription also commemorates their immediate family who were never given a grave.

“We are inviting the souls of our exterminated family to rest in our grave.”

[Webmaster: Sadly, Sigi passed away, in Melbourne, on 18th October 2019, at the age of 95.]

Sources:

Story by Margaret Burin

Australian Broadcasting Commission

News 24 TV

and

Material reproduced here

with the kind permission of

Sigi and Hanka Siegreich

Write a Tribute

Write a Tribute

- for the "Lives & Legends" section of our website

their grandparents or other members of their nuclear or extended family,

who either survived or perished in the Holocaust.

- In fact, anyone who wishes to may write a tribute page to some or all of their family,

so long as their family comes from Częstochowa or the surrounding area.

- Each tribute should be a maximum of 1,500 words (in WORD or plain text format)

and MUST be accompanied by at least 2 or up to 4 photographs (a page of plain text

without a pic or two does not look good at all)..

- Each tribute should be headed CLEARLY with the names of the people being written about.

- You may submit a tribute for as many families as you wish – but please,

write each one SEPARATELY.

- Please state clearly the name you want to appear as the author of the tribute and,

optionally, your relationship to the family being written about.

All tributes

should be

emailed to

the Webmaster

at

aragorn@axiomcs.com.au